Research Workshop - Jordan From Palestinian Archaeology to the Archaeology of the Nakba: Exploring New Directions

Dr. Brian Boyd, Columbia University, USA. Dr. Mazen Iwaisi, Queen’s University Belfast, UK. Mr. Jamal Barghouth, (Al-Mashhad, Palestinian Institute of Cultural Landscape Studies), Palestine.

Prof. Omar al-Ghul (Yarmuk University. Dr. Mazen Iwaisi, Queen’s University Belfast, UK. Dr. Johnny Mansour (Association for the Defense of the Rights of Internally Displaced People. Ali Habiballah (Independent Historian).

Makbula Nassar (Association for the Defense of the Rights of Internally Displaced People). “Wikipedia: An Accessible Tool for Counteracting Memoricide”. Dr. Johnny Mansour (Association for the Defense of the Rights of Internally Displaced People). “Churches of the depopulated/destroyed villages in the Nakba of 1948”. Dr. Ramez Eid (Independent Anthropologist) “Anthropology and the Study of the Palestinian Mushaa ‘’commons’’ System”. Ali Habiballah (Independent Historian) ‘’Al-Hula Lake: Drying up the Water, drying up the Culture and Memory’’. Dr. Heba Yazbak (Independent Sociologist). “Displaced and Marginalized Palestinian Cities: The Case of Tiberias”. Khalid Awwad (Association for the Defense of the Rights of Internally Displaced People). “Appropriation and expropriation employed by Israeli leadership during and after their 1948 occupation of Palestinian villages”. Fathi Marshud (Association for the Defense of the Rights of Internally Displaced People). ‘’The Map of Arab Haifa: 3D Project’’. Jad Abu Saed (Independent Archaeologist). “Deir Aban Village: Reclaiming a Place of 1948 Destroyed Palestinian Village”. Majd Sayed-Ahmed (Independent Architect): “Beit Jibrin: A Spatial Reconstruction of a 1948 Destroyed Village”. Prof. Omar al-Ghul (Yarmuk University): “The Stratification of Toponyms in Palestine”. Dr. Brian Boyd (Columbia University) “From British Colonial Archaeology to the ongoing Nakba at Shuqba, West Bank”. Rama Ghanem (Columbia University): “Cinema & Archives – Screening A Cave Is a Pinhole: On Image, Erasure, and the Reconstruction of Memory”. Hala Abu-Helal: (Independent Architect): “The Reconstruction and Revival of Imwas”.

Karim Yehia (Triangle Research& Development Center- Zahrawy Society): “Digital Documentation of Architectural Heritage”. Ram Sari’ (Independent Archaeologist): “The Vanishing of Amwas and the Core of Dispossession”. Liyan Abassi, Batool Schweiki (Independent Archaeologists) "Colonial Archaeo-Tourism in the Nahr al-Auja Basin: Recovering Palestinian Villages Destroyed in 1948". Mr. Jamal Barghouth (PICLS): “A Spatial Disruption? Colonial Archaeologists and the “Ahali” (Peasants and Bedouins) in Palestine 1800-1950”. Dr. Mazen Iwaisi (Queen’s University Belfast). “Deconstructing the Colonial Epistemological Statusquo: The Archaeology of the Nakba and the Palestinian Argumentation”.

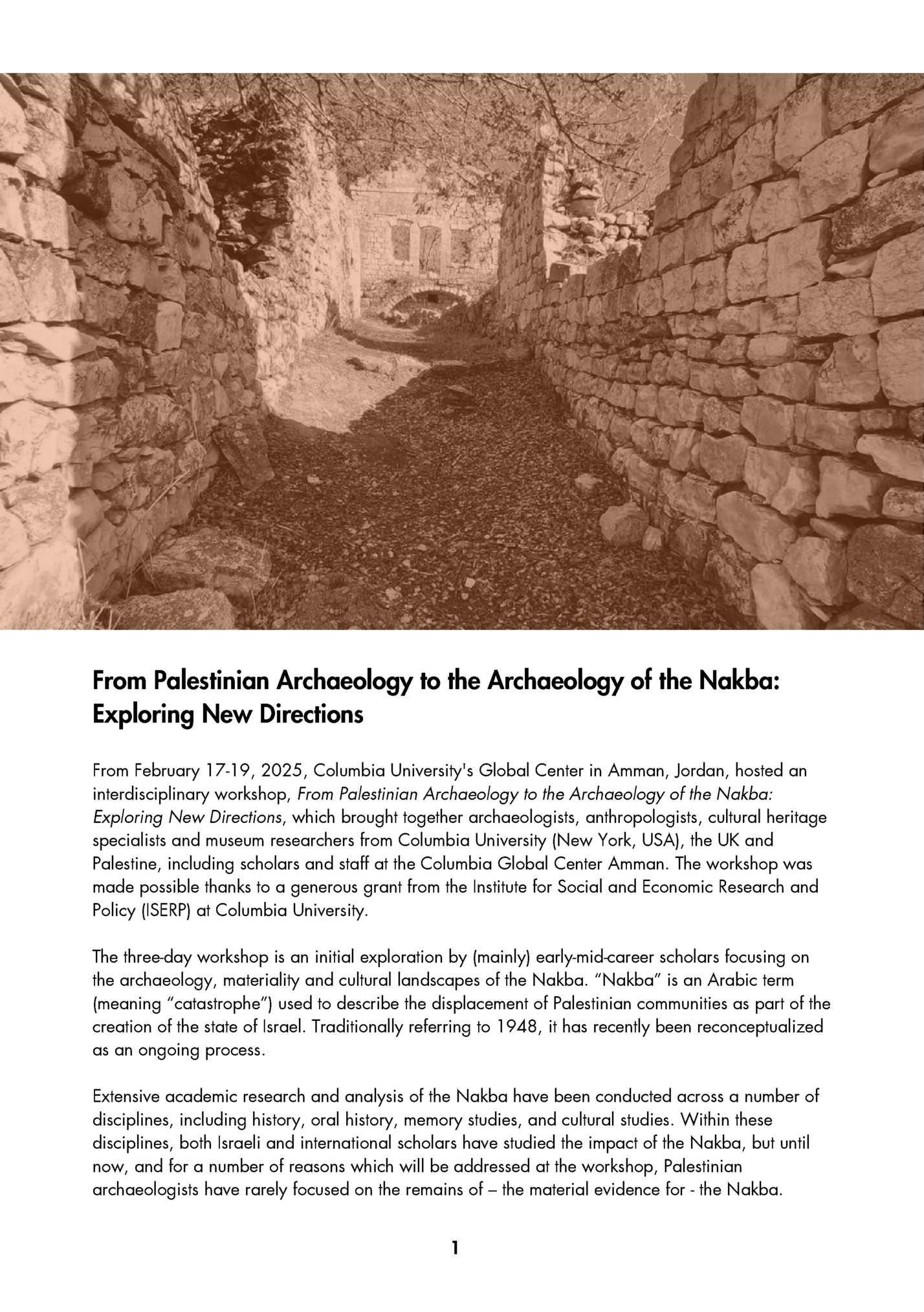

Exploring New Directions From February 17-19, 2025, Columbia University's Global Center in Amman, Jordan, hosted an interdisciplinary workshop, From Palestinian Archaeology to the Archaeology of the Nakba: Exploring New Directions, which brought together archaeologists, anthropologists, cultural heritage specialists and museum researchers from Columbia University (New York, USA), the UK and Palestine, including scholars and staff at the Columbia Global Center Amman. The workshop was made possible thanks to a generous grant from the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy (ISERP) at Columbia University. The three-day workshop is an initial exploration by (mainly) early-mid-career scholars focusing on the archaeology, materiality and cultural landscapes of the Nakba. “Nakba” is an Arabic term (meaning “catastrophe”) used to describe the displacement of Palestinian communities as part of the creation of the state of Israel. Traditionally referring to 1948, it has recently been reconceptualized as an ongoing process. Extensive academic research and analysis of the Nakba have been conducted across a number of disciplines, including history, oral history, memory studies, and cultural studies. Within these disciplines, both Israeli and international scholars have studied the impact of the Nakba, but until now, and for a number of reasons which will be addressed at the workshop, Palestinian archaeologists have rarely focused on the remains of – the material evidence for - the Nakba. 1

move, we believe it is imperative to integrate robust, contemporary archaeological methods and theories into interdisciplinary Nakba studies. There is an urgency here, as the available sources— human memory and material traces—diminish with the passing of generations who experienced the Nakba first-hand. To approach the Nakba from an archaeological perspective and for Palestinian archaeological research to firmly position itself within contemporary critical debates, new initiatives must be launched by upcoming generations of Palestinian scholars and their allies. To this end, the workshop provides a venue for examining the Palestinian Nakba through the lens of 21st archaeological theory and practice, offering diverse perspectives from within the social sciences, the arts and the humanities. Over three days of panel sessions, the workshop explored the following issues: *the material culture of everyday lives and diasporic objects, the architectural remains of “disappeared” villages and rural landscapes; *concepts of space and place in Palestinian landscape archaeology; *the implications of the concept of modernity in Ottoman and British Mandate antiquities laws; the influence of (settler) colonial perspectives on place which exclude the traditional Palestinian village from questions about the recent and deeper past; *the emergence of museums in Palestine within the framework of colonialism and the quasi-state apparatus of the Palestinian Authority; *the relationships between museums and representations of the Nakba; *the looting of property and antiquities from Palestinian villages and cities, and the destination of these items, including to Israeli museums, kibbutzim, and international cultural institutions; *maps and cartography in Palestine, from the traditional to the digital, and their use in Nakba landscape studies; *the concept of remains, as opposed to “ruins”; *the Nakba and the digital humanities. The wars in Gaza, and the ongoing precarity of the situation in the West Bank, has made it almost impossible for both Palestinian and foreign scholars to conduct archaeological fieldwork in the region. It is difficult to assess the amount of erasure and damage being caused to cultural heritage and archaeology. It is difficult to focus on archaeology amidst the massive destruction and loss of life, but as archaeologists, we are also committed to preserving cultural heritage, as a central element of Palestinian identity and hopes for the future. A new generation of Palestinian scholars and activists are now engaging in discussions with colleagues globally to critically reassess the current state of archaeology in Palestine. The aim of these discussions - and of this workshop - is to further establish collaborative international networks that can provide support to Palestinian archaeologists and raise global awareness about the destruction and erasure of Palestinian archaeological sites and, crucially, cultural landscapes and heritage, that lie at the very heart of Palestinians’ deep historical attachment to land and place. Ultimately, our objective is to ensure that future generations have access to their cultural history and heritage, thereby fostering a sense of shared identity and hopeful continuity in the midst of war and uncertainty. 2

The emergence of the archaeology of the Nakba represents more than just a new subfield of archaeological study. It constitutes a fundamental challenge to colonial epistemologies while offering new ways to understand how material evidence contributes to historical understanding and collective memory. This emerging field demonstrates how archaeology can engage with contemporary political issues while maintaining scientific rigor and theoretical sophistication. The workshop "From Palestinian Archaeology to the Archaeology of the Nakba" brought together diverse scholarly approaches that collectively challenge colonial archaeological frameworks while establishing new methodologies for documenting Palestinian material heritage. The contributions reveal how archaeological theory and practice can be decolonized through critical interventions that center Palestinian experiences and perspectives. The theoretical foundations for this emergent field were established by scholars like Dr. Mazen Iwaisi, who proposed decolonial methodologies that recognize the Nakba as a legitimate archaeological subject, while Jamal Barghouth analyzed how colonial archaeologists historically disrupted local (Ahali) knowledge systems and spatial relationships. Dr. Brian Boyd's examination of Shuqba demonstrated how British colonial archaeological practices continue to influence contemporary interpretations and restrict access to Palestinian heritage sites. Documentation of destroyed villages and urban centers featured prominently across multiple contributions. Hala Abu-Helal's detailed reconstruction plan for Imwas preserves building footprints as an open museum while reimagining social spaces, complemented by Majd Sayed-Ahmed's architectural study of Beit Jibrin that respects original urban patterns while planning for sustainable return and growth. Dr. Johnny Mansour documented churches in depopulated villages, preserving evidence of Christian Palestinian presence, while Dr. Heba Yazbak traced the marginalization of Palestinian urban heritage through her case study of Tiberias. Environmental dimensions of erasure were powerfully illustrated by Ali Habiballah's investigation of Al-Hula's dual catastrophes—forced depopulation and water resource destruction—showing how ecological transformation served to erase cultural memory tied to water-based lifeways. This environmental perspective was further developed by Dr. Ramez Eid's anthropological analysis of the traditional Mushaa commons system, revealing how communal land management practices reflected cultural values disrupted by displacement. Digital humanities and technological approaches emerged as crucial methodological innovations. Karim Yehia demonstrated advanced 3D documentation techniques for endangered architectural heritage, while Makbula Nassar presented Wikipedia as a platform for countering memoricide by restoring original place names and geographic knowledge. Rama Ghanem's experimental video work explored how cinema and archives can reconstruct fragmented memories and histories of archaeological plunder. 3

Khalid Awwad, who analyzed systematic expropriation methods employed during and after 1948, and Ram Sari', whose study of Amwas revealed the core mechanisms of Palestinian dispossession. Prof. Omar al-Ghul's exploration of layered toponyms in Palestine demonstrated how place names reflect historical continuities and political contestations, while Layan Abassi and Batool Schweiki exposed how Israeli national parks along the al-Auja River function as sites of colonial archaeotourism that physically overlay destroyed Palestinian villages. Collectively, these contributions establish the archaeology of the Nakba as a critical intervention that integrates material evidence with oral histories, documents processes of erasure and resistance and creates new possibilities for reclaiming Palestinian heritage through innovative documentation methods and theoretical frameworks. Their work demonstrates how archaeology can engage with contemporary political realities while maintaining scientific rigour and creating pathways for cultural reclamation and continuity. Decolonizing Archaeological Practice The colonial foundations of archaeological practice in Palestine have systematically marginalized Palestinian perspectives and experiences. The Archaeological Tell Theory (ATT), heavily reliant on biblical and classical narratives, established research questions aligned with these narratives while excluding traditional Palestinian villages from questions about the recent and deeper past. This theoretical framework reinforced a dichotomy between the archaeological tell and the traditional village, centralizing research on the former while marginalizing the latter. This dichotomy became particularly evident after 1948 when hundreds of traditional Palestinian villages and urban centers were destroyed while archaeological tells were preserved due to their perceived biblical significance. The contrast between pre-Nakba and post-Nakba archaeological approaches to sites like Tell al-Safi, Tell al-Jazar, and Tell Zakaria—and their adjacent villages—reveals how colonial archaeology navigated the presence of living Palestinian communities as obstacles to excavation rather than as subjects worthy of study in their own right. Decolonizing archaeological practice requires challenging these established hierarchies and developing new methodological approaches that integrate Palestinian perspectives, experiences, and knowledge systems. As Albert Glock demonstrated through his excavations at Ti'innik near Jenin from 1985 to 1987, this shift represents a complete departure from previous biblical interests in favour of focusing on more recent Ottoman settlements and the continuous presence of Palestinians in the landscape. 4

Fleepit Digital © 2021