Improved oral hygiene care is associated with decreased risk of occurrence for atrial fibrillation and heart failure: A nationwide population-based cohort study European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2020, Vol. 27(17) 1835–1845 ! The European Society of Cardiology 2019 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/2047487319886018 journals.sagepub.com/home/cpr Abstract Aims: Poor oral hygiene can provoke transient bacteremia and systemic inflammation, a mediator of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. This study aims to investigate association of oral hygiene indicators with atrial fibrillation and heart failure risk in Korea. Methods: We included 161,286 subjects from the National Health Insurance System-Health Screening Cohort who had no missing data for demographics, past history, or laboratory findings. They had no history of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, or cardiac valvular diseases. For oral hygiene indicators, presence of periodontal disease, number of tooth brushings, any reasons of dental visit, professional dental cleaning, and number of missing teeth were investigated. Results: During median follow-up of 10.5 years, 4911 (3.0%) cases of atrial fibrillation and 7971 (4.9%) cases of heart failure occurred. In multivariate analysis after adjusting age, sex, socioeconomic status, regular exercise, alcohol consumption, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, current smoking, renal disease, history of cancer, systolic blood pressure, blood and urine laboratory findings, frequent tooth brushing (!3 times/day) was significantly associated with attenuated risk of atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio: 0.90, 95% confidence interval (0.83–0.98)) and heart failure (0.88, (0.82–0.94)). Professional dental cleaning was negatively (0.93, (0.88–0.99)), while number of missing teeth !22 was positively (1.32, (1.11–1.56)) associated with risk of heart failure. Conclusion: Improved oral hygiene care was associated with decreased risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Healthier oral hygiene by frequent tooth brushing and professional dental cleaning may reduce risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Keywords Oral hygiene, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, disease free survival, population study Received 4 August 2019; accepted 10 October 2019 Introduction Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia that is closely associated with risk of systemic embolism, hospitalization, and death.1–4 It is also a well-known major risk factor for occurrence and recurrence of stroke and stroke-related mortality.5 With the current aging population and associated increase of concomitant vascular risk factors and/or cardiovascular disease, the burden of AF is increasing in Western and Asian populations.6–9 Heart failure 1 Department of Neurology, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Korea 2 Department of Neurology, Seoul Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Korea 3 Department of Critical Care Medicine, Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, Korea 4 Clinical Research Center, Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Korea *These authors contributed equally as first authors. Corresponding author: Tae-Jin Song, Department of Neurology, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, 1071 Anyangcheon-ro, Yangcheon-gu, Seoul, 07985, Korea. Email: knstar@ewha.ac.kr Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 Yoonkyung Chang1,*, Ho Geol Woo2,*, Jin Park3,*, Ji Sung Lee4 and Tae-Jin Song1

Methods Subjects The National Health Insurance System (NHIS) covers demographics, socioeconomic status, type of health insurance coverage, medical database for diagnosis, and treatment modality. It provides a nation-supported health examination database and a medical care institution database through random sampling of health information for 50 m Koreans.22 In Korea, the NHIS is the sole insurance provider. It is controlled and supported by the Korean government. It covers approximately 97% of the Korean population. The remaining 3% are supported by the Medical Aid program. Subscribers of the NHIS are recommended to receive standardized medical health examinations every two years.23 We enrolled subjects from the National Health Insurance System-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS).24 The NHIS-HEALS cohort enrolled subjects who participated in medical health screening programs. Their height, weight, laboratory tests, questionnaires on lifestyle, oral health disease, and oral hygiene behaviors were all obtained by the NHIS. The oral health disease and oral hygiene behaviors screening program was provided to subscribers aged !40 years. It consisted of a self-reported questionnaire regarding information about dental symptoms, any dental visits at last year, and oral hygiene behavior. Subjects were investigated by dentists for presence of periodontal disease and condition of teeth including number of missing teeth. If there were dental problems, oral hygiene care was recommended to participants if necessary.23 Our study was based on data from the NHISHEALS. Subjects were enrolled from 2003–2004, who were aged between 40–79 years. All subjects had routine medical examinations including previous history of medical illness, body weight, height, blood pressure measurements, laboratory tests, and lifestyle questionnaire. The total number of recruited subjects was 514,866. Among them, subjects with missing data for variables such as oral health status (n ¼ 343,037) or variables in health examination (n ¼ 8094) and subjects with previous history of AF, HF, or cardiac valvular diseases (n ¼ 2449) were excluded. Finally, 161,286 subjects were analyzed in this study (Supplementary Material Figure 1). This study was approved by the Ewha Womans University of College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (approval number: EUMC 2018-01-067). Informed consent was waived because retrospective anonymized data were used. Study variables and definitions Information on smoking habits and alcohol consumption was obtained by questionnaire. Body mass index was defined as the participant’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of the participant’s height in meters. Regular physical exercise was considered to be strenuous physical activity performed for at least 20 minutes more than once per week. Economic status was dichotomized at the bottom 10% level. Hypertension was defined using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases Related Health Problems (ICD)-10 codes I10–I11 and the prescription of an antihypertensive agent with at least one claim per year.22,25 Diabetes mellitus was defined using ICD–10 codes E10–E14 and the prescription of an antidiabetic medication with at least one claim per year. Dyslipidemia was defined using ICD-10 code E78 and the prescription of a lipid-lowering agent with at least one claim per year. Renal disease was considered as using ICD–10 codes N18.1–N18.5 and N18.9 with at least one claim per year. Malignancy was defined as using ICD-10 codes C00–D48 with at least one claim per year. Subjects were examined by dentists as part of routine health check-up.25 Periodontal disease was considered Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 (HF) is a clinical syndrome accompanied by decreased ability of cardiac contraction or pumping and/or filling with blood.10 HF is also one of the most frequent cardiovascular diseases worldwide. The prevalence of HF is continuously increasing. Despite recent advances for treatment and prevention for HF, HF-related morbidity and mortality remain as high as ever.11 Therefore, it is important to identify and control risk factors or causative factors of AF and HF. Up to now, risk factors such as hypertension, coronary artery occlusive disease, cardiomyopathy, alcohol consumption, and smoking have been identified.12,13 However, information about other modifiable risk factors is lacking.14,15 Periodontal disease is common in the general population. It is closely related to oral hygiene behavior such as tooth brushing.16 Indicators of oral hygiene include presence of periodontal disease, number of tooth brushing per day, professional dental cleaning, and number of missing teeth.17–19 Poor oral hygiene can provoke transient bacteremia and systemic inflammation, an immune process known to be a mediator of AF and HF.20,21 However, studies regarding the association of oral hygiene indicators with occurrence of AF and HF are lacking. We hypothesized that improved oral hygiene care would be associated with decreased risk of AF and HF. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the association of oral hygiene indicators with risk of AF and HF in a nation-wide general population based longitudinal study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 27(17)

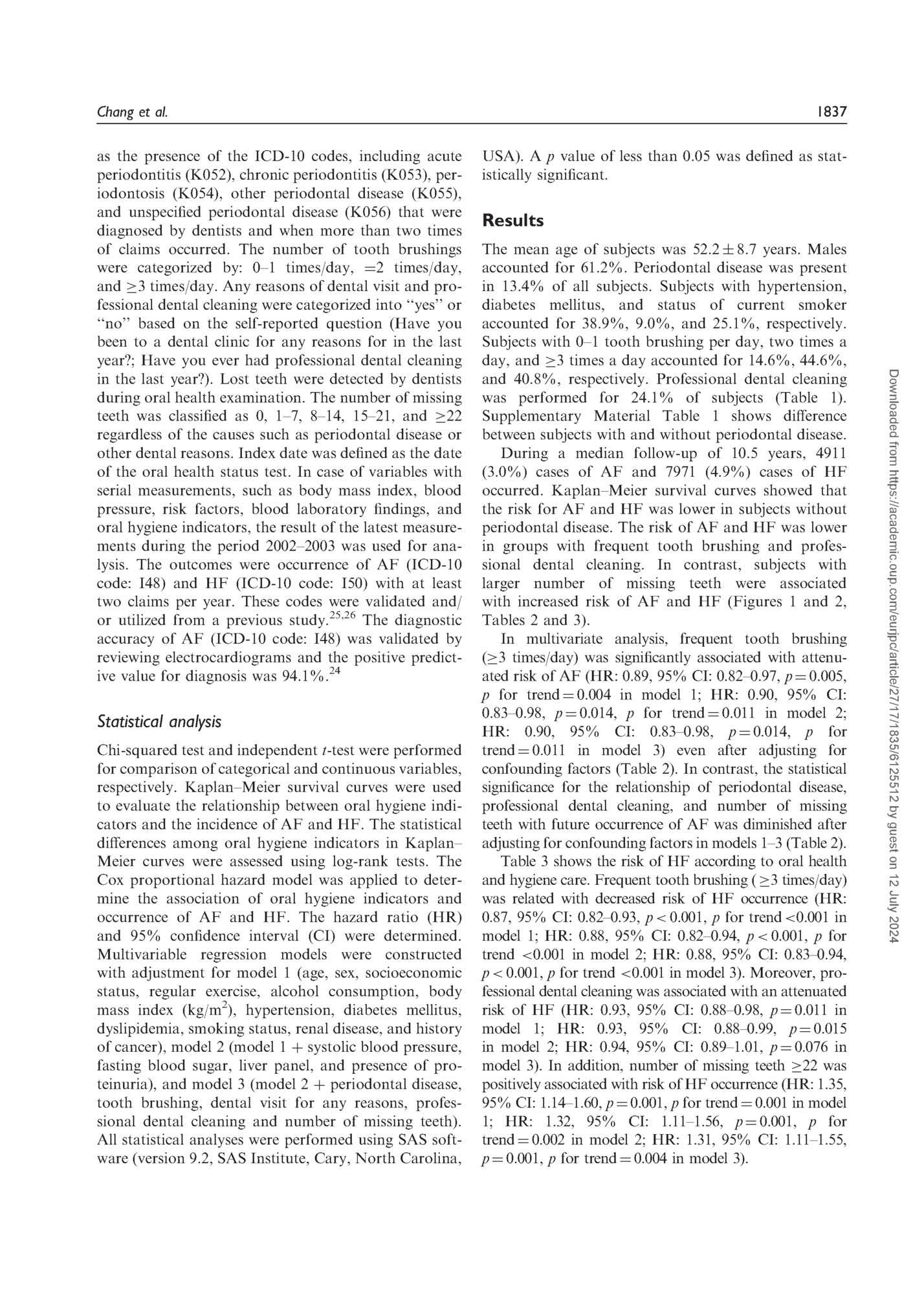

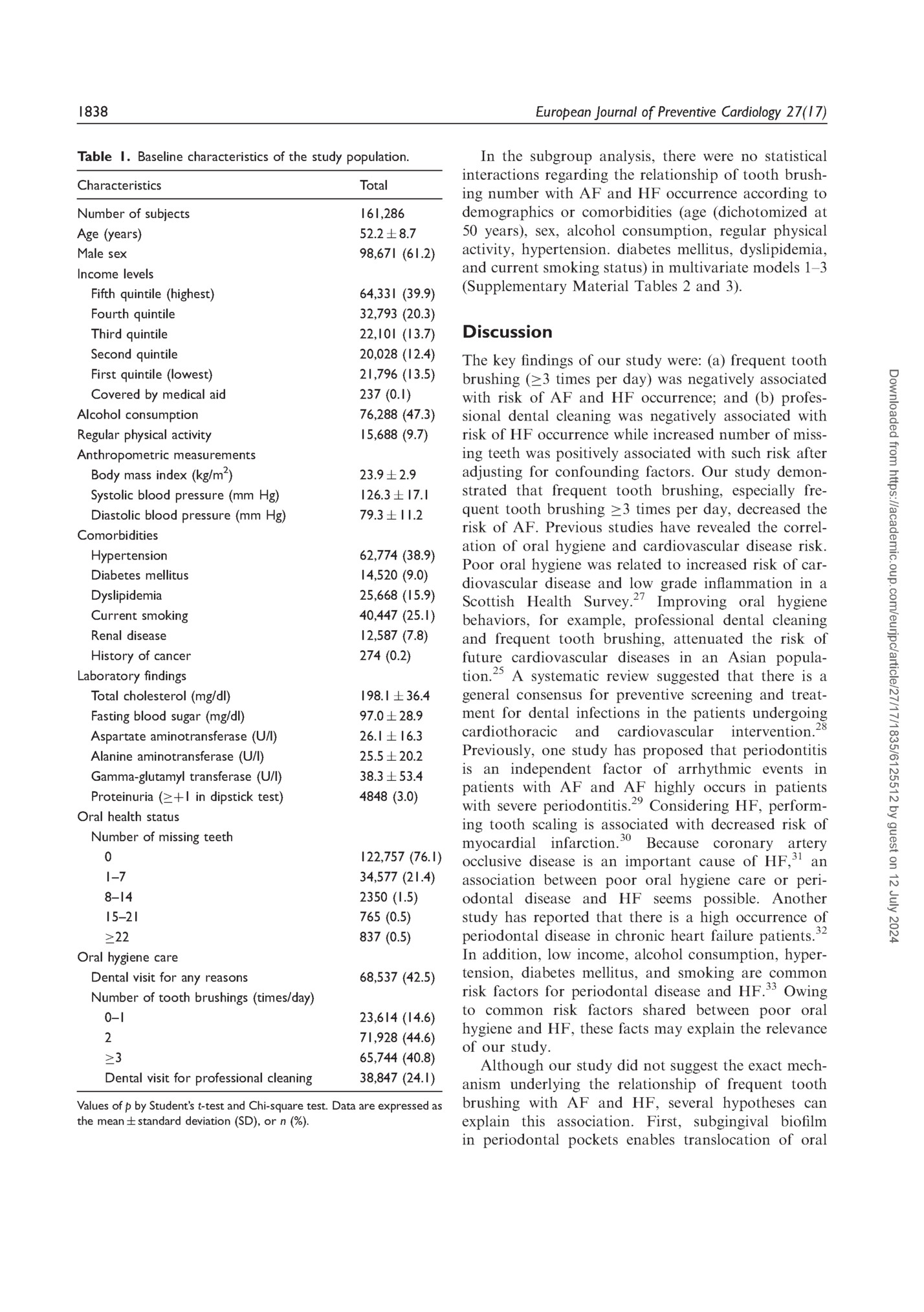

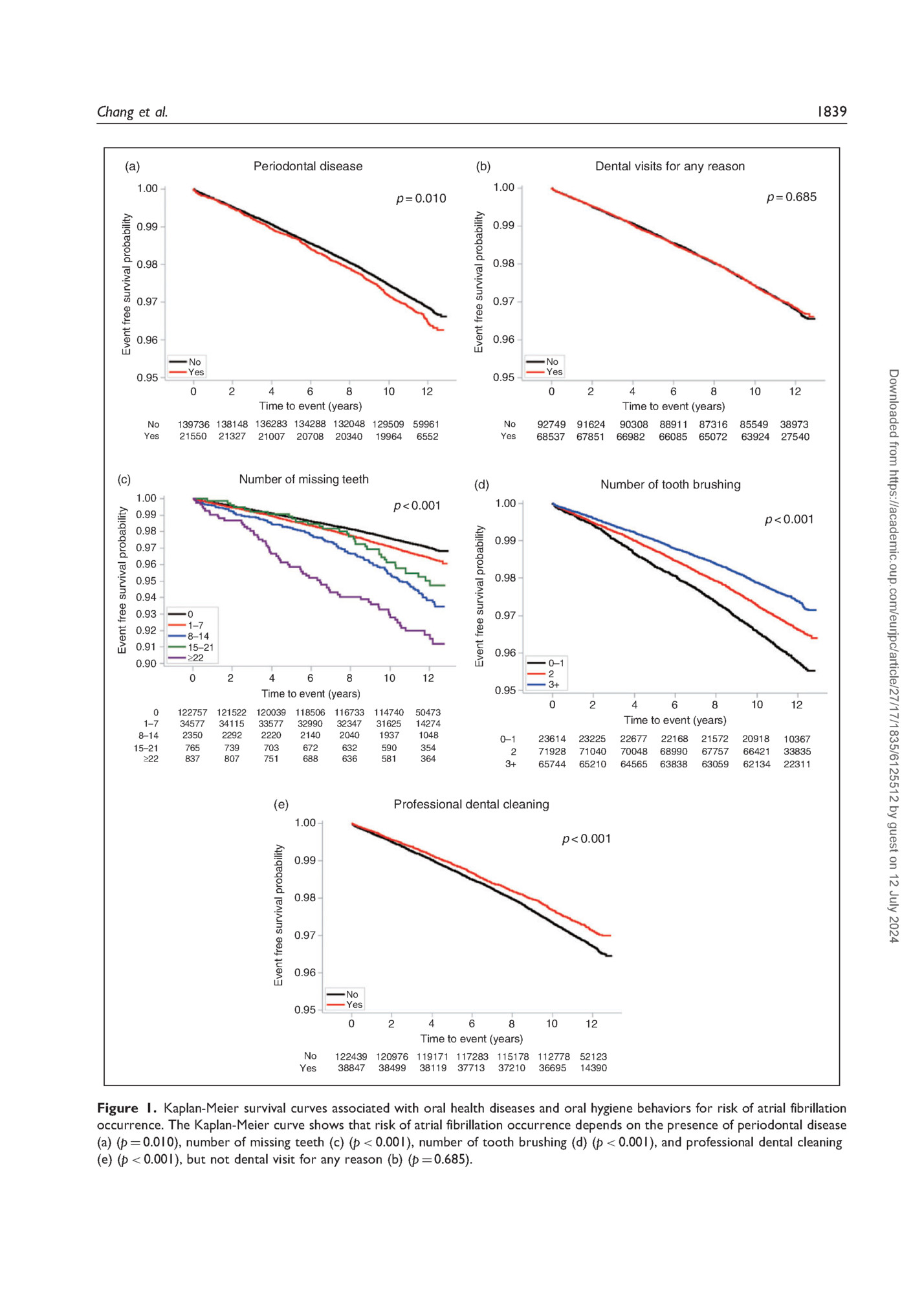

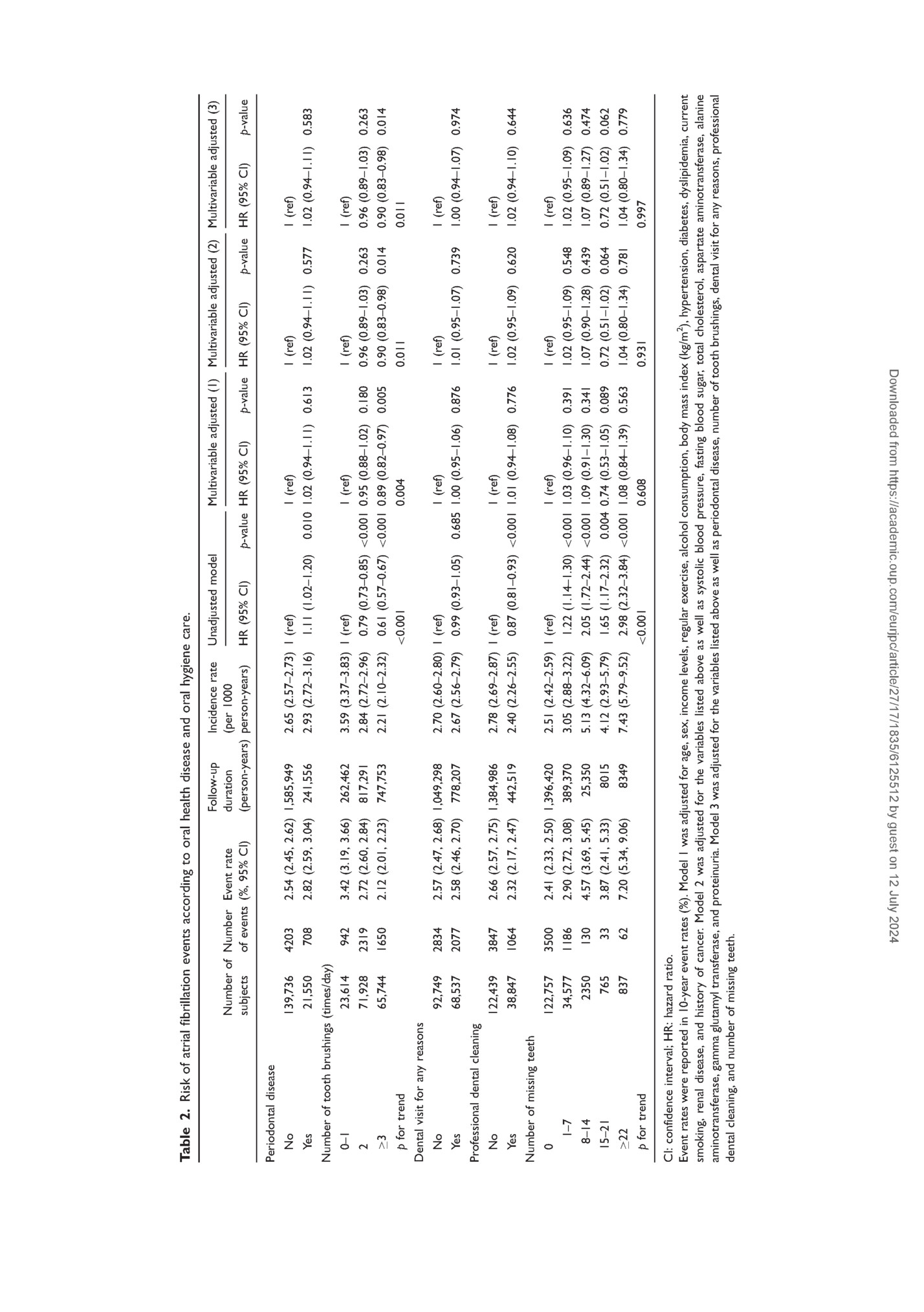

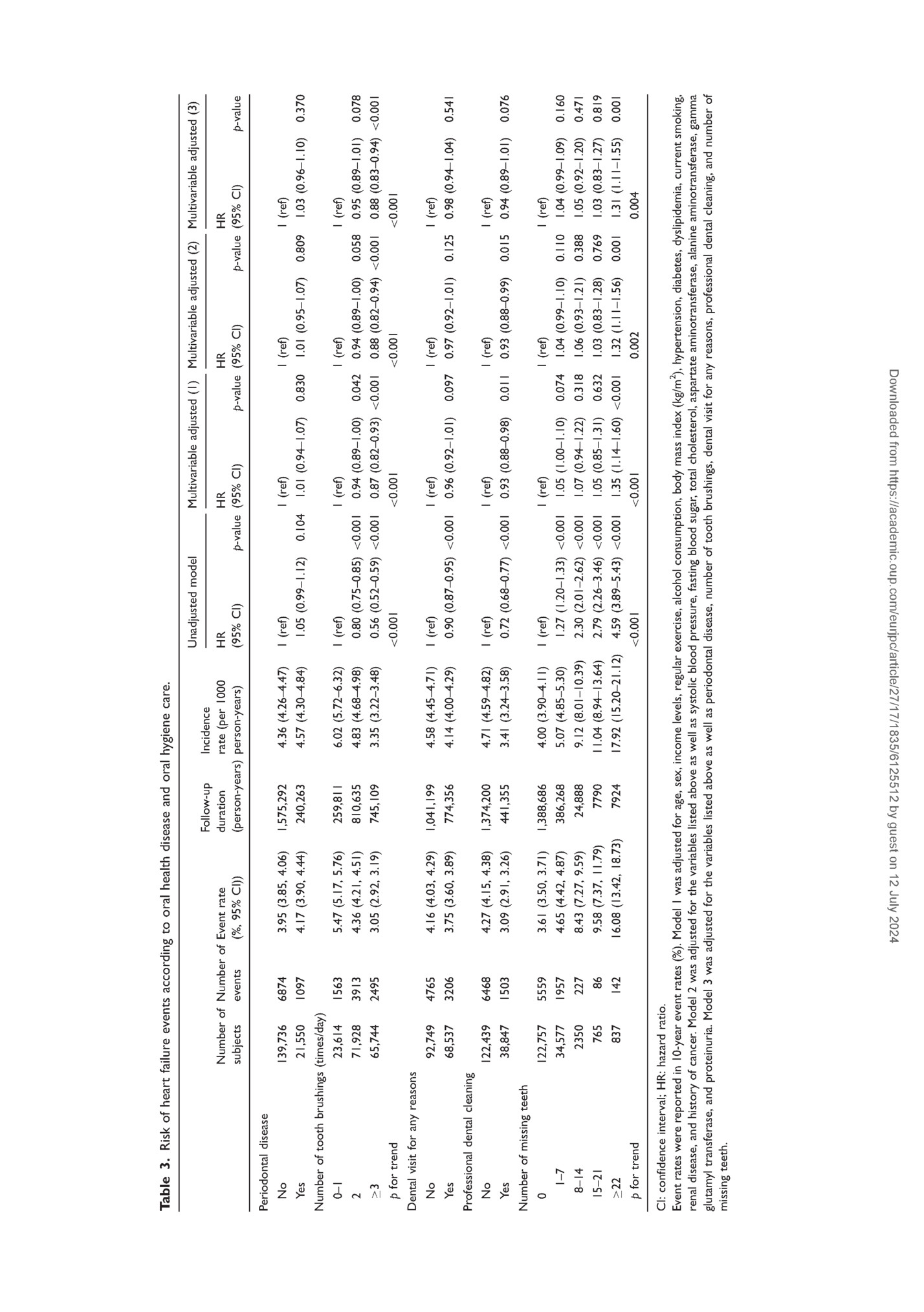

Statistical analysis Chi-squared test and independent t-test were performed for comparison of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to evaluate the relationship between oral hygiene indicators and the incidence of AF and HF. The statistical differences among oral hygiene indicators in Kaplan– Meier curves were assessed using log-rank tests. The Cox proportional hazard model was applied to determine the association of oral hygiene indicators and occurrence of AF and HF. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined. Multivariable regression models were constructed with adjustment for model 1 (age, sex, socioeconomic status, regular exercise, alcohol consumption, body mass index (kg/m2), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking status, renal disease, and history of cancer), model 2 (model 1 þ systolic blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, liver panel, and presence of proteinuria), and model 3 (model 2 þ periodontal disease, tooth brushing, dental visit for any reasons, professional dental cleaning and number of missing teeth). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A p value of less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Results The mean age of subjects was 52.2 Æ 8.7 years. Males accounted for 61.2%. Periodontal disease was present in 13.4% of all subjects. Subjects with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and status of current smoker accounted for 38.9%, 9.0%, and 25.1%, respectively. Subjects with 0–1 tooth brushing per day, two times a day, and !3 times a day accounted for 14.6%, 44.6%, and 40.8%, respectively. Professional dental cleaning was performed for 24.1% of subjects (Table 1). Supplementary Material Table 1 shows difference between subjects with and without periodontal disease. During a median follow-up of 10.5 years, 4911 (3.0%) cases of AF and 7971 (4.9%) cases of HF occurred. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that the risk for AF and HF was lower in subjects without periodontal disease. The risk of AF and HF was lower in groups with frequent tooth brushing and professional dental cleaning. In contrast, subjects with larger number of missing teeth were associated with increased risk of AF and HF (Figures 1 and 2, Tables 2 and 3). In multivariate analysis, frequent tooth brushing (!3 times/day) was significantly associated with attenuated risk of AF (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.82–0.97, p ¼ 0.005, p for trend ¼ 0.004 in model 1; HR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.83–0.98, p ¼ 0.014, p for trend ¼ 0.011 in model 2; HR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.83–0.98, p ¼ 0.014, p for trend ¼ 0.011 in model 3) even after adjusting for confounding factors (Table 2). In contrast, the statistical significance for the relationship of periodontal disease, professional dental cleaning, and number of missing teeth with future occurrence of AF was diminished after adjusting for confounding factors in models 1–3 (Table 2). Table 3 shows the risk of HF according to oral health and hygiene care. Frequent tooth brushing ( !3 times/day) was related with decreased risk of HF occurrence (HR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.82–0.93, p < 0.001, p for trend <0.001 in model 1; HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.82–0.94, p < 0.001, p for trend <0.001 in model 2; HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.83–0.94, p < 0.001, p for trend <0.001 in model 3). Moreover, professional dental cleaning was associated with an attenuated risk of HF (HR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.98, p ¼ 0.011 in model 1; HR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.99, p ¼ 0.015 in model 2; HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89–1.01, p ¼ 0.076 in model 3). In addition, number of missing teeth !22 was positively associated with risk of HF occurrence (HR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.14–1.60, p ¼ 0.001, p for trend ¼ 0.001 in model 1; HR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.11–1.56, p ¼ 0.001, p for trend ¼ 0.002 in model 2; HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.11–1.55, p ¼ 0.001, p for trend ¼ 0.004 in model 3). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 as the presence of the ICD-10 codes, including acute periodontitis (K052), chronic periodontitis (K053), periodontosis (K054), other periodontal disease (K055), and unspecified periodontal disease (K056) that were diagnosed by dentists and when more than two times of claims occurred. The number of tooth brushings were categorized by: 0–1 times/day, ¼2 times/day, and !3 times/day. Any reasons of dental visit and professional dental cleaning were categorized into ‘‘yes’’ or ‘‘no’’ based on the self-reported question (Have you been to a dental clinic for any reasons for in the last year?; Have you ever had professional dental cleaning in the last year?). Lost teeth were detected by dentists during oral health examination. The number of missing teeth was classified as 0, 1–7, 8–14, 15–21, and !22 regardless of the causes such as periodontal disease or other dental reasons. Index date was defined as the date of the oral health status test. In case of variables with serial measurements, such as body mass index, blood pressure, risk factors, blood laboratory findings, and oral hygiene indicators, the result of the latest measurements during the period 2002–2003 was used for analysis. The outcomes were occurrence of AF (ICD-10 code: I48) and HF (ICD-10 code: I50) with at least two claims per year. These codes were validated and/ or utilized from a previous study.25,26 The diagnostic accuracy of AF (ICD-10 code: I48) was validated by reviewing electrocardiograms and the positive predictive value for diagnosis was 94.1%.24 1837

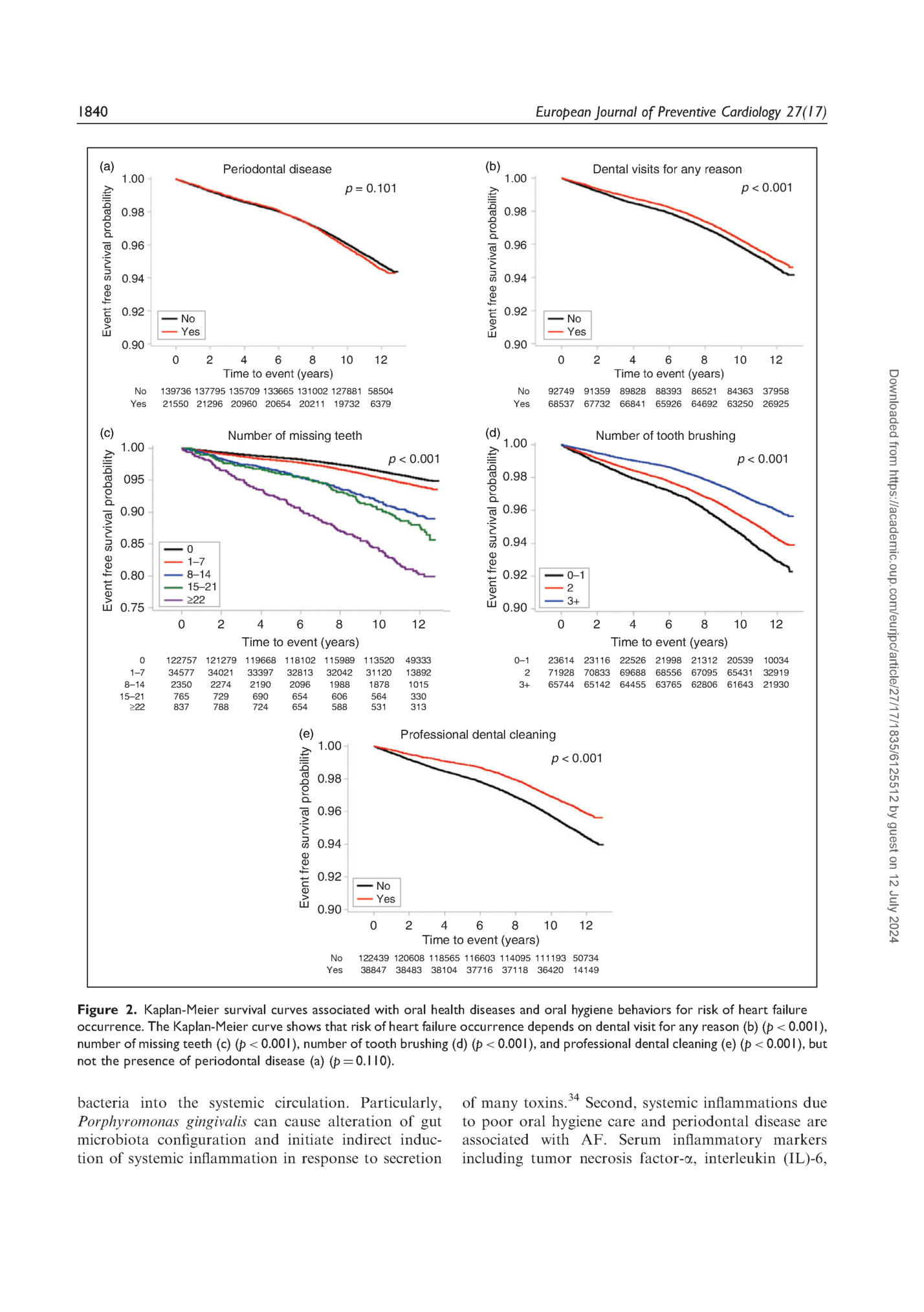

European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 27(17) Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population. Total Number of subjects Age (years) Male sex Income levels Fifth quintile (highest) Fourth quintile Third quintile Second quintile First quintile (lowest) Covered by medical aid Alcohol consumption Regular physical activity Anthropometric measurements Body mass index (kg/m2) Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) Comorbidities Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Dyslipidemia Current smoking Renal disease History of cancer Laboratory findings Total cholesterol (mg/dl) Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl) Aspartate aminotransferase (U/l) Alanine aminotransferase (U/l) Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/l) Proteinuria (!þ1 in dipstick test) Oral health status Number of missing teeth 0 1–7 8–14 15–21 !22 Oral hygiene care Dental visit for any reasons Number of tooth brushings (times/day) 0–1 2 !3 Dental visit for professional cleaning 161,286 52.2 Æ 8.7 98,671 (61.2) 64,331 (39.9) 32,793 (20.3) 22,101 (13.7) 20,028 (12.4) 21,796 (13.5) 237 (0.1) 76,288 (47.3) 15,688 (9.7) 23.9 Æ 2.9 126.3 Æ 17.1 79.3 Æ 11.2 62,774 (38.9) 14,520 (9.0) 25,668 (15.9) 40,447 (25.1) 12,587 (7.8) 274 (0.2) 198.1 Æ 36.4 97.0 Æ 28.9 26.1 Æ 16.3 25.5 Æ 20.2 38.3 Æ 53.4 4848 (3.0) 122,757 (76.1) 34,577 (21.4) 2350 (1.5) 765 (0.5) 837 (0.5) 68,537 (42.5) 23,614 71,928 65,744 38,847 (14.6) (44.6) (40.8) (24.1) Values of p by Student’s t-test and Chi-square test. Data are expressed as the mean Æ standard deviation (SD), or n (%). Discussion The key findings of our study were: (a) frequent tooth brushing (!3 times per day) was negatively associated with risk of AF and HF occurrence; and (b) professional dental cleaning was negatively associated with risk of HF occurrence while increased number of missing teeth was positively associated with such risk after adjusting for confounding factors. Our study demonstrated that frequent tooth brushing, especially frequent tooth brushing !3 times per day, decreased the risk of AF. Previous studies have revealed the correlation of oral hygiene and cardiovascular disease risk. Poor oral hygiene was related to increased risk of cardiovascular disease and low grade inflammation in a Scottish Health Survey.27 Improving oral hygiene behaviors, for example, professional dental cleaning and frequent tooth brushing, attenuated the risk of future cardiovascular diseases in an Asian population.25 A systematic review suggested that there is a general consensus for preventive screening and treatment for dental infections in the patients undergoing cardiothoracic and cardiovascular intervention.28 Previously, one study has proposed that periodontitis is an independent factor of arrhythmic events in patients with AF and AF highly occurs in patients with severe periodontitis.29 Considering HF, performing tooth scaling is associated with decreased risk of myocardial infarction.30 Because coronary artery occlusive disease is an important cause of HF,31 an association between poor oral hygiene care or periodontal disease and HF seems possible. Another study has reported that there is a high occurrence of periodontal disease in chronic heart failure patients.32 In addition, low income, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking are common risk factors for periodontal disease and HF.33 Owing to common risk factors shared between poor oral hygiene and HF, these facts may explain the relevance of our study. Although our study did not suggest the exact mechanism underlying the relationship of frequent tooth brushing with AF and HF, several hypotheses can explain this association. First, subgingival biofilm in periodontal pockets enables translocation of oral Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 Characteristics In the subgroup analysis, there were no statistical interactions regarding the relationship of tooth brushing number with AF and HF occurrence according to demographics or comorbidities (age (dichotomized at 50 years), sex, alcohol consumption, regular physical activity, hypertension. diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status) in multivariate models 1–3 (Supplementary Material Tables 2 and 3).

1839 (a) Periodontal disease (b) 1.00 0.99 0.98 0.97 0.96 2 4 6 8 Time to event (years) Number of missing teeth 0.97 0.96 0.95 0.94 0 1–7 8–14 15–21 t22 0 0 1–7 8–14 15–21 t22 No Yes No Yes 2 92749 68537 91624 67851 (d) 0.98 0.90 0.96 0 2 4 6 8 Time to event (years) 10 121522 34115 2292 739 807 120039 118506 116733 33577 32990 32347 2220 2140 2040 703 672 632 751 688 636 114740 31625 1937 590 581 50473 14274 1048 354 364 90308 66982 88911 66085 87316 65072 10 12 85549 63924 38973 27540 Number of tooth brushing p < 0.001 0.99 0.98 0.97 0.96 12 122757 34577 2350 765 837 4 6 8 Time to event (years) 1.00 p < 0.001 0.99 0.91 0.97 12 Event free survival probability Event free survival probability 10 139736 138148 136283 134288 132048 129509 59961 21550 21327 21007 20708 20340 19964 6552 1.00 0.92 0.98 0.95 (c) 0.93 0.99 0.95 0–1 2 3+ 0 0–1 2 3+ 2 23614 71928 65744 23225 71040 65210 4 6 8 Time to event (years) 22677 70048 64565 22168 68990 63838 21572 67757 63059 10 12 20918 66421 62134 10367 33835 22311 Professional dental cleaning (e) Event free survival probability 1.00 p < 0.001 0.99 0.98 0.97 0.96 0.95 No Yes 0 No Yes 2 4 6 8 Time to event (years) 10 122439 120976 119171 117283 115178 112778 38847 38499 38119 37713 37210 36695 12 52123 14390 Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves associated with oral health diseases and oral hygiene behaviors for risk of atrial fibrillation occurrence. The Kaplan-Meier curve shows that risk of atrial fibrillation occurrence depends on the presence of periodontal disease (a) (p ¼ 0.010), number of missing teeth (c) (p < 0.001), number of tooth brushing (d) (p < 0.001), and professional dental cleaning (e) (p < 0.001), but not dental visit for any reason (b) (p ¼ 0.685). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 No Yes 0 No Yes p = 0.685 p = 0.010 Event free survival probability Event free survival probability 1.00 0.95 Dental visits for any reason

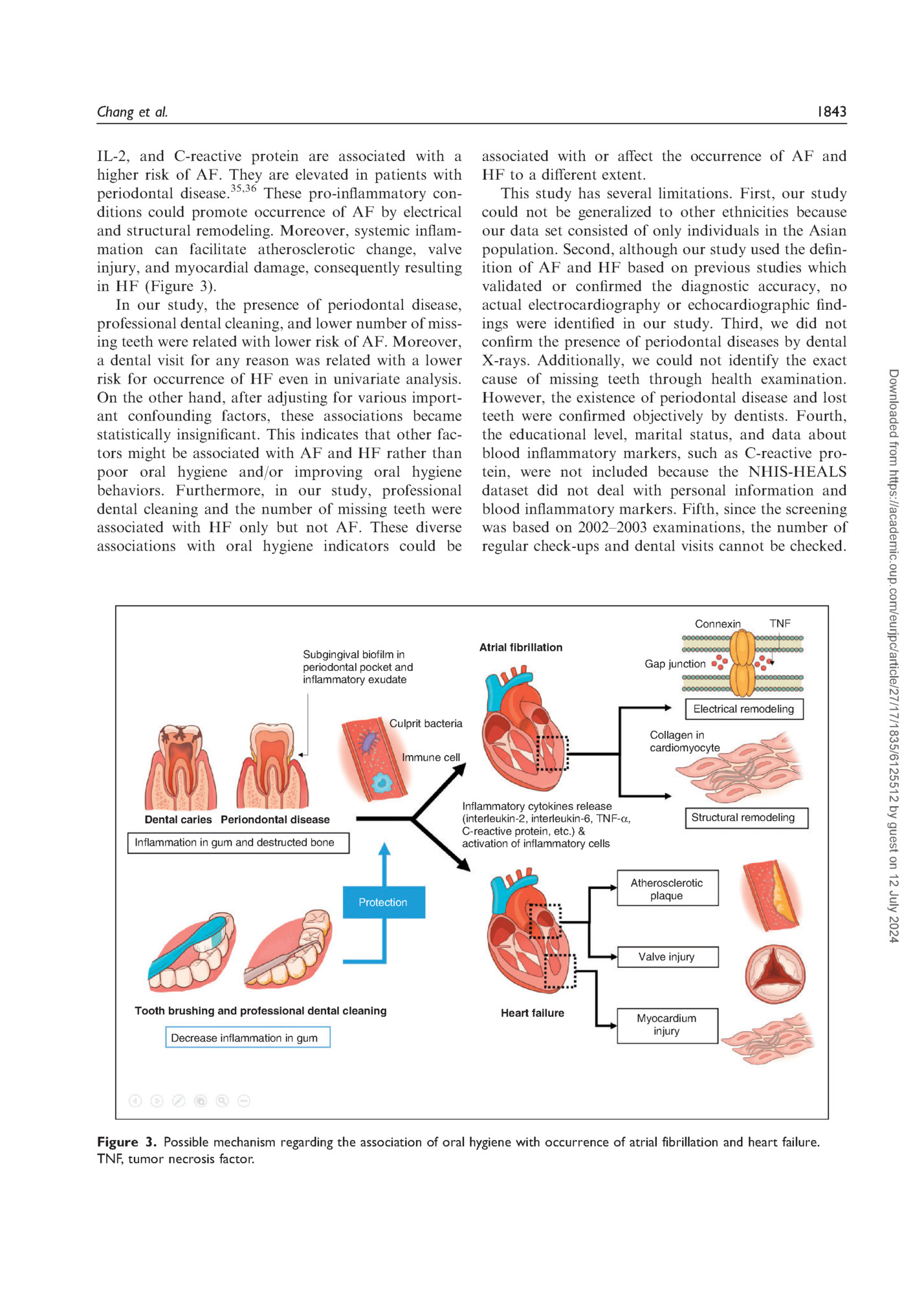

European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 27(17) (a) 0.98 0.96 0.94 0.92 No Yes 0 2 0.94 0.92 No Yes 12 0 139736 137795 135709 133665 131002 127881 58504 21550 21296 20960 20654 20211 19732 6379 No Yes (d) Number of missing teeth 1.00 p < 0.001 095 0.90 0.85 0 1–7 8–14 15–21 ≥22 0.80 0.75 0 2 4 6 8 Time to event (years) 10 122757 121279 119668 118102 115989 113520 34577 34021 33397 32813 32042 31120 2274 1878 1988 2096 2190 2350 729 564 606 654 690 765 788 531 588 654 724 837 Event free survival probability (e) Event free survival probability Event free survival probability 0.96 2 92749 68537 91359 67732 89828 66841 88393 65926 86521 64692 84363 63250 12 37958 26925 Number of tooth brushing 1.00 p < 0.001 0.98 0.96 0.94 0.92 0–1 2 3+ 0.90 12 49333 13892 1015 330 313 4 6 8 10 Time to event (years) 0 0–1 2 3+ 2 23614 71928 65744 23116 70833 65142 4 6 8 10 Time to event (years) 22526 69688 64455 21998 68556 63765 21312 67095 62806 20539 65431 61643 12 10034 32919 21930 Professional dental cleaning 1.00 p < 0.001 0.98 0.96 0.94 0.92 0.90 No Yes 0 No Yes 2 4 6 8 10 Time to event (years) 12 122439 120608 118565 116603 114095 111193 50734 38847 38483 38104 37716 37118 36420 14149 Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves associated with oral health diseases and oral hygiene behaviors for risk of heart failure occurrence. The Kaplan-Meier curve shows that risk of heart failure occurrence depends on dental visit for any reason (b) (p < 0.001), number of missing teeth (c) (p < 0.001), number of tooth brushing (d) (p < 0.001), and professional dental cleaning (e) (p < 0.001), but not the presence of periodontal disease (a) (p ¼ 0.110). bacteria into the systemic circulation. Particularly, Porphyromonas gingivalis can cause alteration of gut microbiota configuration and initiate indirect induction of systemic inflammation in response to secretion of many toxins.34 Second, systemic inflammations due to poor oral hygiene care and periodontal disease are associated with AF. Serum inflammatory markers including tumor necrosis factor-a, interleukin (IL)-6, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 4 6 8 10 Time to event (years) (c) 0 1–7 8–14 15–21 ≥22 0.98 0.90 0.90 No Yes Dental visits for any reason p < 0.001 1.00 p = 0.101 Event free survival probability Event free survival probability (b) Periodontal disease 1.00

Yes 33 62 765 837 !22 817,291 747,753 262,462 241,556 778,207 442,519 7.20 (5.34, 9.06) 3.87 (2.41, 5.33) 4.57 (3.69, 5.45) 2.90 (2.72, 3.08) 8349 8015 25,350 389,370 2.41 (2.33, 2.50) 1,396,420 2.32 (2.17, 2.47) 2.66 (2.57, 2.75) 1,384,986 2.58 (2.46, 2.70) 2.57 (2.47, 2.68) 1,049,298 2.72 (2.60, 2.84) 2.12 (2.01, 2.23) 3.42 (3.19, 3.66) 2.82 (2.59, 3.04) 2.54 (2.45, 2.62) 1,585,949 HR (95% CI) Unadjusted model 1.11 (1.02–1.20) <0.001 0.99 (0.93–1.05) 7.43 (5.79–9.52) 4.12 (2.93–5.79) 5.13 (4.32–6.09) 3.05 (2.88–3.22) 1 (ref) 0.685 1.00 (0.95–1.06) 0.876 1 (ref) 0.004 0.004 0.74 (0.53–1.05) 0.089 <0.001 0.608 2.98 (2.32–3.84) <0.001 1.08 (0.84–1.39) 0.563 1.65 (1.17–2.32) 2.05 (1.72–2.44) <0.001 1.09 (0.91–1.30) 0.341 1.22 (1.14–1.30) <0.001 1.03 (0.96–1.10) 0.391 1 (ref) 0.87 (0.81–0.93) <0.001 1.01 (0.94–1.08) 0.776 2.51 (2.42–2.59) 1 (ref) 2.40 (2.26–2.55) 2.78 (2.69–2.87) 1 (ref) 2.67 (2.56–2.79) 1 (ref) p-value 1 (ref) p-value HR (95% CI) 1 (ref) 1.02 (0.94–1.11) 0.577 0.011 1 (ref) 0.011 0.96 (0.89–1.03) 0.263 0.90 (0.83–0.98) 0.014 1.07 (0.89–1.27) 0.474 0.72 (0.51–1.02) 0.062 1.04 (0.80–1.34) 0.779 0.997 1.07 (0.90–1.28) 0.439 1 (ref) 1.02 (0.95–1.09) 0.620 1.02 (0.95–1.09) 0.636 1.02 (0.94–1.10) 0.644 1 (ref) 1.02 (0.95–1.09) 0.548 1 (ref) 1.01 (0.95–1.07) 0.739 1 (ref) 1.00 (0.94–1.07) 0.974 1 (ref) 0.96 (0.89–1.03) 0.263 0.90 (0.83–0.98) 0.014 1 (ref) 1.02 (0.94–1.11) 0.583 1 (ref) p-value HR (95% CI) 0.010 1.02 (0.94–1.11) 0.613 1 (ref) p-value HR (95% CI) Multivariable adjusted (1) Multivariable adjusted (2) Multivariable adjusted (3) 0.79 (0.73–0.85) <0.001 0.95 (0.88–1.02) 0.180 0.61 (0.57–0.67) <0.001 0.89 (0.82–0.97) 0.005 2.70 (2.60–2.80) 1 (ref) 2.84 (2.72–2.96) 2.21 (2.10–2.32) 3.59 (3.37–3.83) 1 (ref) 2.93 (2.72–3.16) 2.65 (2.57–2.73) 1 (ref) Follow-up Incidence rate duration (per 1000 (person-years) person-years) 0.72 (0.51–1.02) 0.064 1.04 (0.80–1.34) 0.781 0.931 CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio. Event rates were reported in 10-year event rates (%). Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income levels, regular exercise, alcohol consumption, body mass index (kg/m2), hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, current smoking, renal disease, and history of cancer. Model 2 was adjusted for the variables listed above as well as systolic blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, total cholesterol, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, gamma glutamyl transferase, and proteinuria. Model 3 was adjusted for the variables listed above as well as periodontal disease, number of tooth brushings, dental visit for any reasons, professional dental cleaning, and number of missing teeth. p for trend 130 2350 8–14 3500 15–21 122,757 1064 3847 1186 1–7 38,847 2077 2834 2319 1650 942 708 4203 34,577 0 Yes Number of missing teeth No 122,439 Yes Professional dental cleaning 68,537 No Dental visit for any reasons 92,749 71,928 65,744 2 !3 p for trend 23,614 0–1 Number of tooth brushings (times/day) 21,550 No Periodontal disease Number of Number Event rate subjects of events (%, 95% CI) Table 2. Risk of atrial fibrillation events according to oral health disease and oral hygiene care. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024

122,757 5559 86 142 765 837 15–21 !22 p for trend 16.08 (13.42, 18.73) 9.58 (7.37, 11.79) 8.43 (7.27, 9.59) 4.65 (4.42, 4.87) 3.61 (3.50, 3.71) 3.09 (2.91, 3.26) 4.27 (4.15, 4.38) 3.75 (3.60, 3.89) 4.16 (4.03, 4.29) 3.05 (2.92, 3.19) 4.36 (4.21, 4.51) 7924 7790 24,888 386,268 1,388,686 441,355 1,374,200 774,356 1,041,199 745,109 810,635 259,811 240,263 1,575,292 17.92 (15.20–21.12) 11.04 (8.94–13.64) 9.12 (8.01–10.39) 5.07 (4.85–5.30) 4.00 (3.90–4.11) 3.41 (3.24–3.58) 4.71 (4.59–4.82) 4.14 (4.00–4.29) 4.58 (4.45–4.71) 3.35 (3.22–3.48) 4.83 (4.68–4.98) 6.02 (5.72–6.32) 4.57 (4.30–4.84) 4.36 (4.26–4.47) 1.07 (0.94–1.22) 1.05 (0.85–1.31) 2.30 (2.01–2.62) <0.001 2.79 (2.26–3.46) <0.001 0.632 0.318 0.074 0.011 0.097 4.59 (3.89–5.43) <0.001 1.35 (1.14–1.60) <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 1.05 (1.00–1.10) 1 (ref) 0.93 (0.88–0.98) 1 (ref) 0.96 (0.92–1.01) 1 (ref) <0.001 1.27 (1.20–1.33) <0.001 1 (ref) 0.72 (0.68–0.77) <0.001 1 (ref) 0.90 (0.87–0.95) <0.001 1 (ref) <0.001 0.87 (0.82–0.93) <0.001 0.042 0.830 0.56 (0.52–0.59) <0.001 1 (ref) 1.01 (0.94–1.07) 1 (ref) 0.058 0.809 0.110 0.015 0.388 0.769 0.001 1.04 (0.99–1.10) 1 (ref) 0.93 (0.88–0.99) 1 (ref) 1.06 (0.93–1.21) 1.03 (0.83–1.28) 1.32 (1.11–1.56) 0.002 1.31 (1.11–1.55) 0.004 1.03 (0.83–1.27) 1.05 (0.92–1.20) 1.04 (0.99–1.09) 1 (ref) 0.94 (0.89–1.01) 1 (ref) 0.98 (0.94–1.04) 1 (ref) 1 (ref) 0.125 <0.001 <0.001 0.97 (0.92–1.01) 0.078 0.370 p-value 0.001 0.819 0.471 0.160 0.076 0.541 0.88 (0.83–0.94) <0.001 0.95 (0.89–1.01) 1 (ref) 1.03 (0.96–1.10) 1 (ref) HR p-value (95% CI) 0.88 (0.82–0.94) <0.001 0.94 (0.89–1.00) 1 (ref) 1.01 (0.95–1.07) 1 (ref) HR p-value (95% CI) 0.94 (0.89–1.00) 0.104 HR p-value (95% CI) Multivariable adjusted (1) Multivariable adjusted (2) Multivariable adjusted (3) 0.80 (0.75–0.85) <0.001 1 (ref) 1.05 (0.99–1.12) 1 (ref) HR (95% CI) Unadjusted model CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio. Event rates were reported in 10-year event rates (%). Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income levels, regular exercise, alcohol consumption, body mass index (kg/m2), hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, current smoking, renal disease, and history of cancer. Model 2 was adjusted for the variables listed above as well as systolic blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, total cholesterol, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, gamma glutamyl transferase, and proteinuria. Model 3 was adjusted for the variables listed above as well as periodontal disease, number of tooth brushings, dental visit for any reasons, professional dental cleaning, and number of missing teeth. 227 2350 8–14 1957 34,577 1–7 0 Number of missing teeth 1503 6468 38,847 Professional dental cleaning No 122,439 Yes 3206 Yes 4765 68,537 No Dental visit for any reasons 92,749 2495 65,744 !3 p for trend 3913 71,928 2 5.47 (5.17, 5.76) 3.95 (3.85, 4.06) Number of tooth brushings (times/day) 0–1 23,614 1563 6874 4.17 (3.90, 4.44) Yes 1097 21,550 No Periodontal disease Number of Number of Event rate subjects events (%, 95% CI)) Follow-up Incidence duration rate (per 1000 (person-years) person-years) Table 3. Risk of heart failure events according to oral health disease and oral hygiene care. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024

1843 Connexin TNF Atrial fibrillation Subgingival biofilm in periodontal pocket and inflammatory exudate Gap junction Electrical remodeling Culprit bacteria Collagen in cardiomyocyte Immune cell Inflammatory cytokines release (interleukin-2, interleukin-6, TNF-α, C-reactive protein, etc.) & activation of inflammatory cells Dental caries Periondontal disease Inflammation in gum and destructed bone Structural remodeling Atherosclerotic plaque Protection Valve injury Tooth brushing and professional dental cleaning Decrease inflammation in gum Heart failure Myocardium injury Figure 3. Possible mechanism regarding the association of oral hygiene with occurrence of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. TNF, tumor necrosis factor. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/17/1835/6125512 by guest on 12 July 2024 associated with or affect the occurrence of AF and HF to a different extent. This study has several limitations. First, our study could not be generalized to other ethnicities because our data set consisted of only individuals in the Asian population. Second, although our study used the definition of AF and HF based on previous studies which validated or confirmed the diagnostic accuracy, no actual electrocardiography or echocardiographic findings were identified in our study. Third, we did not confirm the presence of periodontal diseases by dental X-rays. Additionally, we could not identify the exact cause of missing teeth through health examination. However, the existence of periodontal disease and lost teeth were confirmed objectively by dentists. Fourth, the educational level, marital status, and data about blood inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, were not included because the NHIS-HEALS dataset did not deal with personal information and blood inflammatory markers. Fifth, since the screening was based on 2002–2003 examinations, the number of regular check-ups and dental visits cannot be checked. IL-2, and C-reactive protein are associated with a higher risk of AF. They are elevated in patients with periodontal disease.35,36 These pro-inflammatory conditions could promote occurrence of AF by electrical and structural remodeling. Moreover, systemic inflammation can facilitate atherosclerotic change, valve injury, and myocardial damage, consequently resulting in HF (Figure 3). In our study, the presence of periodontal disease, professional dental cleaning, and lower number of missing teeth were related with lower risk of AF. Moreover, a dental visit for any reason was related with a lower risk for occurrence of HF even in univariate analysis. On the other hand, after adjusting for various important confounding factors, these associations became statistically insignificant. This indicates that other factors might be associated with AF and HF rather than poor oral hygiene and/or improving oral hygiene behaviors. Furthermore, in our study, professional dental cleaning and the number of missing teeth were associated with HF only but not AF. These diverse associations with oral hygiene indicators could be

Fleepit Digital © 2021