JAKOB JON WILLE SIMON JON ANDREASEN GUNNAR WILLE 2 3

4 PREFACE 5

What is a universe? Chapter 2 How: How do I get an idea for a universe? Chapter 3 Design: How do I illustrate and describe the universe? Chapter 4 Content: How do I produce content in a universe? Chapter 5 Documentation and presentation: How can I create a universe bible? Chapter 6 Formatting: How can I develop formats from a universe? Chapter 7 Publishing and Maintenance: How can I work with audiences across development and releases? Chapter 8 Future and perspective: How can I use universe evolution in the future? 6 7

9

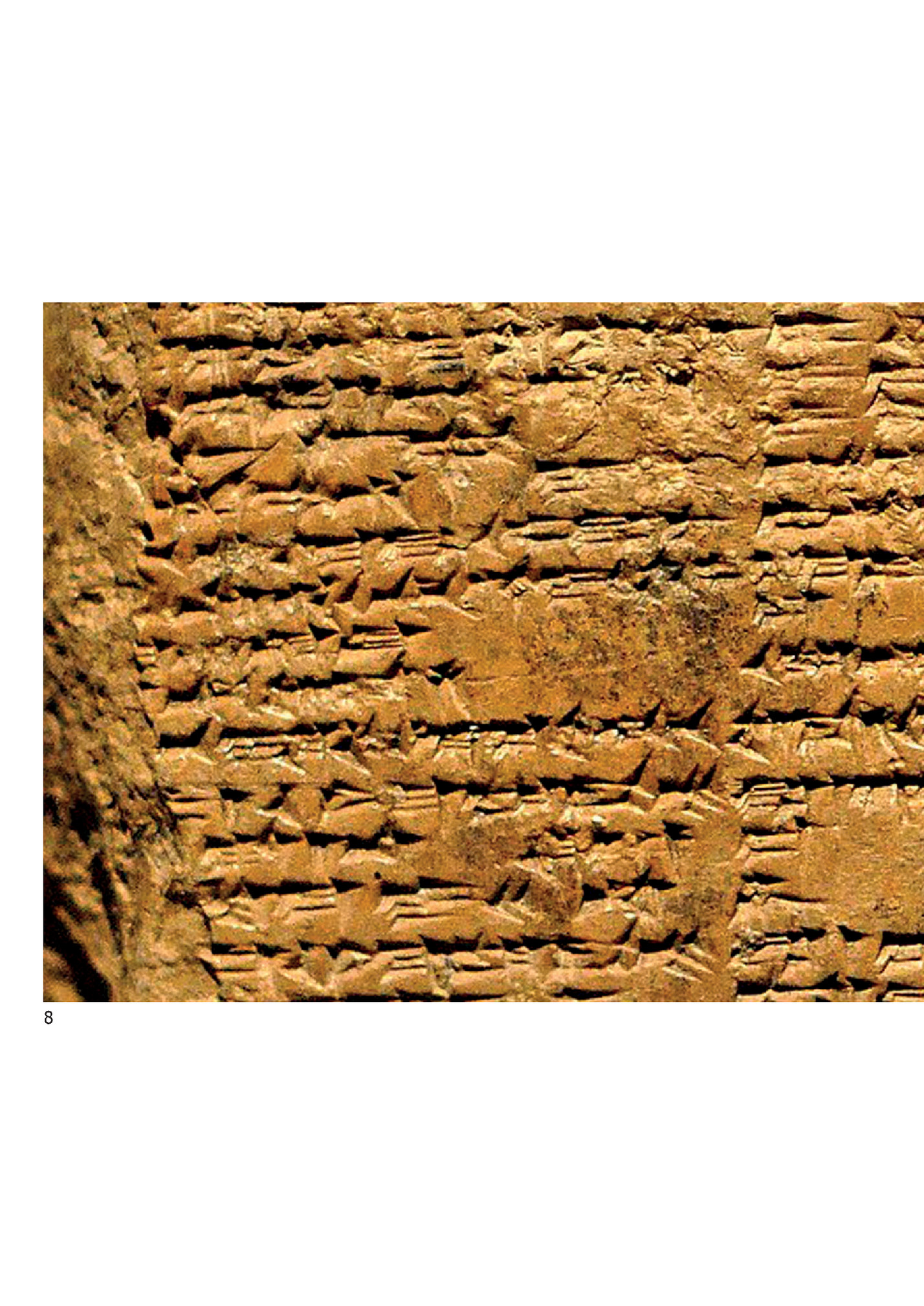

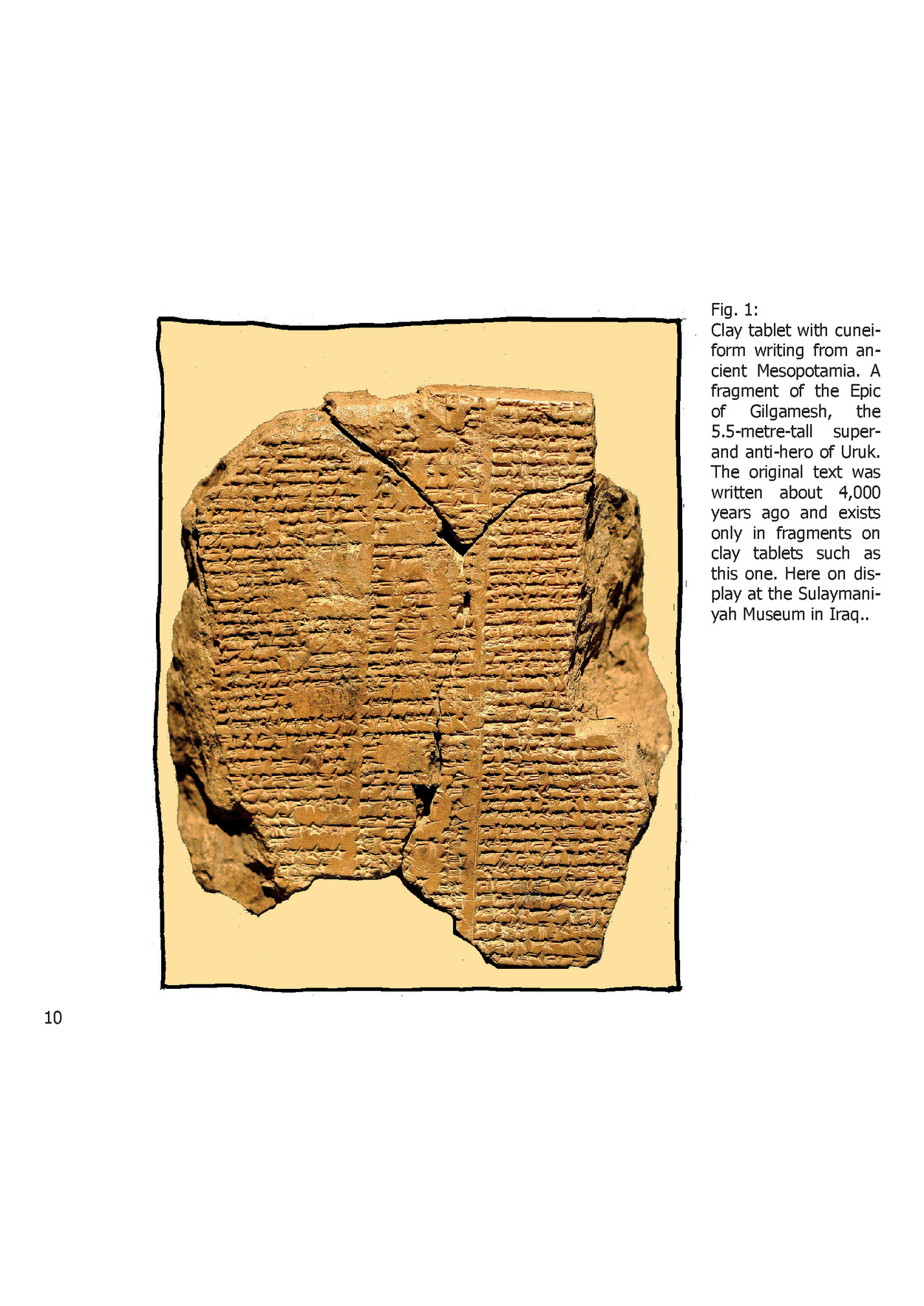

Clay tablet with cuneiform writing from ancient Mesopotamia. A fragment of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the 5.5-metre-tall superand anti-hero of Uruk. The original text was written about 4,000 years ago and exists only in fragments on clay tablets such as this one. Here on display at the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Iraq.. Capitel 1 What Is a Universe? About Stories, Worlds and Universes A map is like a screenplay to me (Wim Wenders, The Logic of Images, 1991: 52) The opening section of one of the oldest and most entertaining texts in literary history, the epic poem of the wilful King Gilgamesh from ancient Mesopotamia, contains a description of the royal city of Uruk. We are invited up onto the city wall to admire the city’s splendour and scale and the beautiful temple, whose secret tablet box contains the text about the Gilgamesh’s exploits. In this double exposure, place and character are introduced in a single movement and blend into one. We understand that the greatness of Gilgamesh and of the city are one and the same. After this introduction, the narrative picks up pace, and we see its 10 world unfolded through Gilgamesh’s outrageous acts and his bromance with the wild man Enkidu. It tells the amazing story of these two superheroes, who put any prejudice about dusty ancient tales to shame. Ultimately, it all ends where it began. The story reaches its conclusion in the city of Uruk, with a look at the protagonist’s altered perspective on life (after the loss of Enkidu) and of Uruk, to which the entire poem may in fact have been a tribute. At least it is easy to perceive the city and its surroundings as the story world. The history of fiction is full of these amazing and unforgettable places, from Asgard to Moominvalley to Gotham 11

the Italian writer Italio Calvino’s Invisible story, and much (sometimes everything) is Cities (1974), are the main attraction; other left over to the imagination times, we mainly experience the place, the Story World Although a story world is an important condition for the story to unfold, as the audience we usually tend instinctively to focus on plot and character relationships. As pointed out by the Danish film scholar Torben Grodal, among others, narrative schemata associated with notions of causality are key to our understanding of human reality and everyday life.1 We understand that things happen for a reason, and if evolutionary biology is to be believed, this ability to plan actions and prepare for possible outcomes based on causal schemata is one of the reasons behind the success of humankind as a species. It is also one of the reasons why we tell stories. Cause-andeffect sequences are the backbone of conventional storytelling, which could be regarded as simulations of possible 12 events. Thus, stories provide us with an opportunity to practice life in a relatively safe setting, for example in a book or on a screen. Although places are a built-in 13

In addressing the issue of the lack ting lost and finding one’s way home – a focus on place or space in conventional of focus on place in our theoretical treat- 14 ment of fiction, the American narratologist Marie-Laure Ryan quotes from E. M. Forster’s 1927 collection of lectures Aspects Of the Novel.3 Forster’s minimal narrative, which has often been used as an example to define the concept of a plot goes as follows: ‘The king died and then the queen died of grief” The plot seemingly gives us everything that we, as an audience, expect: the principal characters (the king and the queen), causality (the queen dies because the king dies) and a theme (grief). Ryan’s point is that the world is absent from Forster’s text. Time and place are left to our imagination. Lacking any precise knowledge about it, we quickly develop mental images. Time may be associated with a period when kings and queens held greater importance than they do today. The Middle Ages, perhaps. We are also quick to imagine a place where the royals live; a palace or a castle. We might also imagine the royal residence embedded in the culture we happen to know best. This assumption is based on what the American philosopher John Searl calls the principle of minimal departure, that absent any other information, we imagine what is most familiar to us. This phenomenon is also known as the reality principle.4 Forster’s mini story is open to all these interpretations, and we construct them so effortlessly that we sometimes overlook their significance. When it comes to visual media, indications of time and place inevitably become more specific. The narration theorist Edward Branigan uses the term story world to describe the so-called diegetic space in film and other moving images that are decoded as part of the process of taking in visual narra15

on the two-dimensional input from the moving images.5 This process is usually so seamless that we do not notice it, and Branigan deserves credit for bring- 16 ing it to our attention. Thus, what Branigan calls a story world may be seen to constitute the story’s spatial dimension. To Branigan, this spatial dimension is a mental construct that the audience creates in order to navigate in the story. However, we may also regard the story world as a combination of narrative and spatial aspects as they are presented to us in a work of fiction. To grasp this view, we might imagine a plus-shaped diagram with a horizontal and a vertical axis. The horizontal axis pertains to time – this is where the plot unfolds; while the vertical axis pertains to site – this is where the plot takes place. The story world is defined by these two axes. The story is tied into both time and a spatial setting. In this sense, the world consists of the interweaving of time and space. The Russian literary theorist Mikhail M. Bakhtin uses the term chronotope to describe this interweaving of time and space in literature,6 from chronos, meaning time, and topos, meaning place. Thus, the chronotope is the interweaving of the two dimensions, similar to a story world. Although Bakthin’s purpose was different, the two mental models resemble each other. Story and world are seen holistically as inseparable, interdependent and mutually contributing parts of a single whole. In the creation of stories, the inspiration sometimes comes from the place and sometimes from events, but the two are often difficult to separate. 17

So far, we have described the story world as something that can be decoded in a work of fiction that somehow – through text or moving images – relays a story that unfolds in time. This is the concept that is generally characterized as a story world. However, in this book we also mention universes. Story world and fictional universe are closely related in meaning, and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. In the book we use them to refer to two overlapping but distinct phenomena. While story world refers to the defined diegetic space that is represented, more or less completely, 18 in a narrative work, universe refers to a broader and more dynamic perception of such a work and what it might include. In this view, for example, the Hundred Acre Wood in A. A. Milne’s series of children’s stories about Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet constitute the story world. However, when the Hundred Acre Wood appears in other media, such as stage productions, film, TV series, games and amusement parks, where it serves as a basis for new stories and images by new authors or fans, it begins to take on the character of a universe. Thus, with the term universe we point to the expanding, genre- and format-transcending transmedial quality of what was originally a world, such as the one in the books about Winnie-the-Pooh. In our view, a story world points inwards, while a universe is more dynamic and inclusive and thus points outwards. While the story world is centripetal, the fictional universe is centrifugal. The American media professor Jason Mittell has similarly described the TV series LOST as a story that expands across media in a way that he characterizes as ‘centrifugal storytelling’.8 Although we use both terms in the book, we prefer universes because it is more dynamic and inclusive. One or more worlds and their various publication formats may be included in a universe that is constantly expanding – just like the actual universe. Thus, we refer to 1) individual worlds associated with a single work of fiction, 2) transmedial worlds or universes, in which the stories extend over multiple publication formats, and 3) ideas about story worlds and fictional universes before they are manifested in various publication formats. The third category is the one in which we form mental or tangible images of the world or universe before it is produced. At least, this is one way to see it 19

Fleepit Digital © 2021