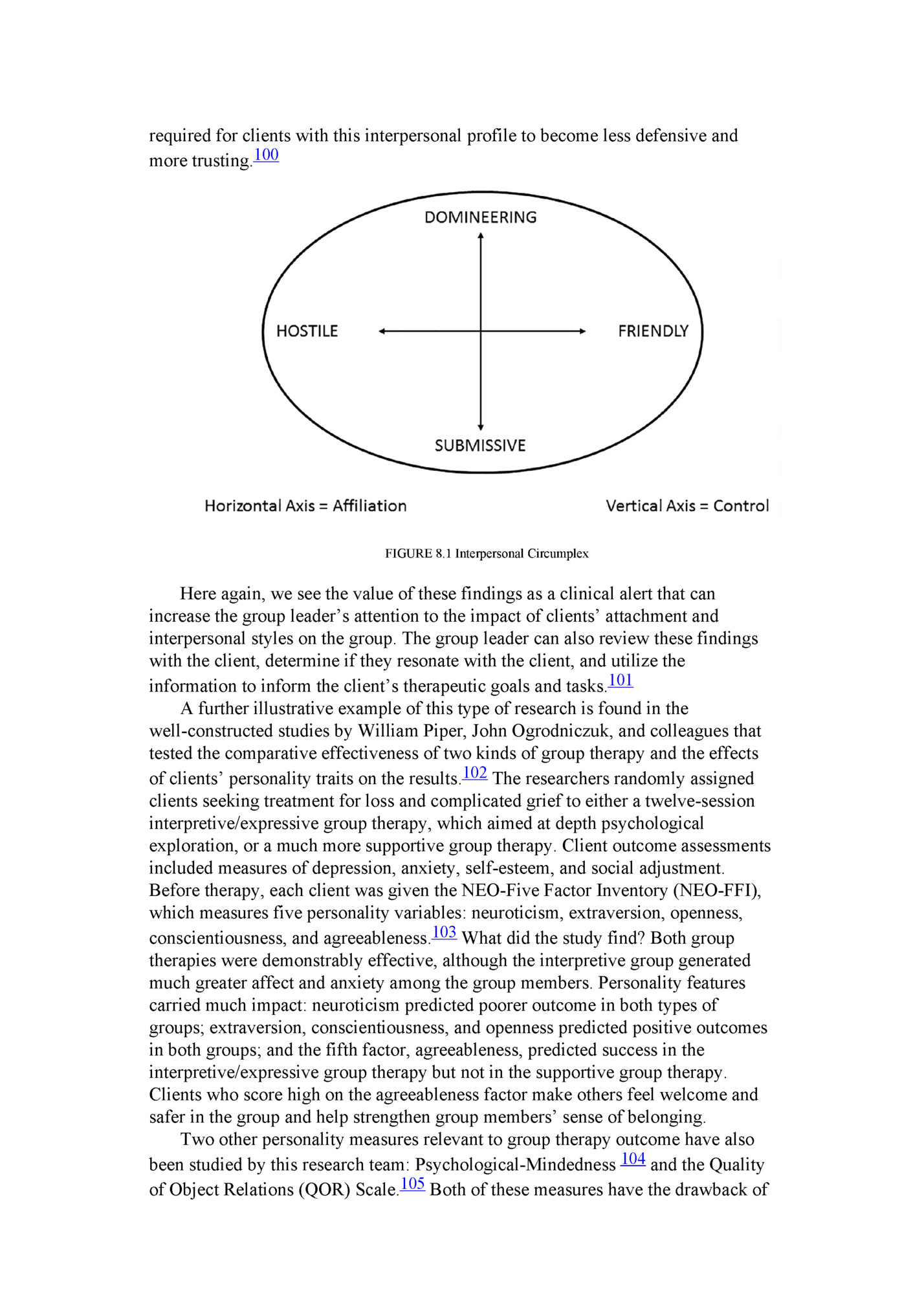

shut,” which she did with great expertise. The results of Anne’s self-report questionnaires confirmed the clinical picture: Anne was a person with a strongly dismissive, avoidant attachment style. She had experienced significant early life adversity, and she now regarded relationships as dangerous and not worth the risk of engagement. After I (ML) shared my formulation and impressions, Anne expressed particular interest in the traumatic roots of her difficulties. Although she did not have symptoms of psychological trauma in the form of flashbacks, intense anxiety symptoms, or hyperarousal, she showed significant interpersonal consequences of early life exposure to physical threat and emotional abuse. At the same time, she recognized that the isolation was unhealthy for her over the long term, and she acknowledged fears of returning to alcohol. She was eager to learn, and her motivation for engagement in group therapy seemed to build as we were able to focus on how group therapy worked. What seemed most helpful to Anne was understanding that the group would be a safe, cohesive environment and would be led by able therapists who would allow her to proceed at a pace that felt safe. The objective of her group work would be to liberate herself from the fear engendered by her father that had influenced all her relationships. The group would aim to increase her zone of safety in relationships, first within the group and then hopefully outside the group. We talked as well about her propensity to distance herself in relationships, acknowledging that the risk for her would be to dismiss others in the group or flee when afraid. In contrast, I noted that her openness and her risk-taking with me boded well for her participation in group therapy. << Interpersonal and Personality Inventories Contemporary interpersonal theorists have attempted to develop a classification of diverse interpersonal styles and behavior based on data gathered through interpersonal inventories (often, the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems—IIP).95 The client’s responses are placed onto a schematic circumplex of interpersonal relations that portrays the client’s tendencies to relate along two key intersecting interpersonal dimensions: control, ranging from domineering to nonassertive/submissive, and affiliation, ranging from warm and overly nurturant to cold (see Figure 8.1).96 Two early studies that used a form of the interpersonal circumplex in a twelve-session training group of graduate psychology students found that hostile, dismissive members were much more likely to experience other group members as hostile. Strongly dominant (domineering) individuals resisted group engagement and tended to devalue or discount the group.97 Subsequent research reinforces these findings. Clients who tend to seek affiliation generally engage well in group therapy, but the pleasure of belonging is not an end in itself and must be utilized to increase the client’s risk-taking within the group.98 Individuals who are dominant and cold typically are more difficult to engage, but interesting work by the group analyst Steiner Lorentzen and colleagues has demonstrated that with proper pregroup preparation and active, supportive group leaders, these dismissive and hard-to-engage clients can do well, even in time-limited interactional group treatments.99 A longer course of treatment may be

more trusting.100 FIGURE 8.1 Interpersonal Circumplex Here again, we see the value of these findings as a clinical alert that can increase the group leader’s attention to the impact of clients’ attachment and interpersonal styles on the group. The group leader can also review these findings with the client, determine if they resonate with the client, and utilize the information to inform the client’s therapeutic goals and tasks.101 A further illustrative example of this type of research is found in the well-constructed studies by William Piper, John Ogrodniczuk, and colleagues that tested the comparative effectiveness of two kinds of group therapy and the effects of clients’ personality traits on the results.102 The researchers randomly assigned clients seeking treatment for loss and complicated grief to either a twelve-session interpretive/expressive group therapy, which aimed at depth psychological exploration, or a much more supportive group therapy. Client outcome assessments included measures of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and social adjustment. Before therapy, each client was given the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), which measures five personality variables: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness.103 What did the study find? Both group therapies were demonstrably effective, although the interpretive group generated much greater affect and anxiety among the group members. Personality features carried much impact: neuroticism predicted poorer outcome in both types of groups; extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness predicted positive outcomes in both groups; and the fifth factor, agreeableness, predicted success in the interpretive/expressive group therapy but not in the supportive group therapy. Clients who score high on the agreeableness factor make others feel welcome and safer in the group and help strengthen group members’ sense of belonging. Two other personality measures relevant to group therapy outcome have also been studied by this research team: Psychological-Mindedness 104 and the Quality of Object Relations (QOR) Scale.105 Both of these measures have the drawback of

interview instead of a client self-report. Psychological-mindednessiii predicts good outcome in all forms of group therapy. Psychologically minded clients are better able to work in therapy—to explore, reflect, and understand.106 Clients with higher QOR scores (i.e., greater maturity in their relationships) are more likely to achieve positive outcomes in interpretive/expressive, emotion-activating group therapy. These clients are also more trusting and able to express a broader range of negative and positive emotions in the group. Clients with low QOR scores are less able to tolerate this more demanding form of therapy and do better in supportive group formats that do not seek to activate distressing emotions.107 Hence there is good evidence that placing clients with very poor relationship capacity into very active and dynamic groups, in the hope that they will benefit from the exposure in the group, is often unsuccessful for the client and has an inhibiting impact on the group. SUMMARY: PREDICTING CLIENT BEHAVIOR Of all the methods used to predict a member’s behavior in a therapy group, the traditional individual intake interview oriented toward establishing a diagnosis is the most limited in its accuracy even though it is the most commonly used. We can enhance its utility, however. Keep in mind that the more the intake procedure resembles the here-and-now focus of the group situation, the more accurate the interviewer’s prediction of a client’s behavior becomes. Hence we recommend that group therapists modify their intake interview to focus on the client’s interpersonal functioning. PRINCIPLES OF GROUP COMPOSITION How do we apply our insights from individual client assessment to the project of composing a group? Group composition is still a soft science. But predictions of how each of our clients is likely to experience the group and of how others will likely experience them in the group helps group therapists to construct more effective groups. Some key findings to consider in composing intensive interactional psychotherapy groups emerge from the empirical and clinical literature and are summarized here: • Clients will re-create their typical relational patterns within the microcosm of the group. This is the essential therapeutic opportunity, and clients should not be discouraged by—but even welcome—the times when their core difficulties emerge in the group. • Clients require a certain amount of interpersonal competence to make the best use of interactional group therapy. • Psychologically minded clients contribute substantially to an interactional therapy group. • Personality and attachment variables are more important predictors of a client’s behavior in a group than diagnosis alone.

questionnaires that add to our understanding of our clients’ ways of interacting. • We can anticipate these interpersonal patterns and address them in pregroup preparation. • Members eager for engagement and willing to take social risks will advance the group’s work. • Clients who are securely attached typically do well in group therapy and promote cohesion. • Clients who are rigidly domineering or dismissive of others may impair the work of the therapy group. This is a cautionary note and not a prohibition, as this risk can be offset by good preparation, therapist flexibility, and empathy. • Clients who have an insecure attachment style will engage in the group in contrasting ways. Some will be anxiously eager for connection and others dismissive and distancing. • Clients who are more rigid, less trusting, and less cooperative will likely struggle with interpersonal exploration and feedback and may require more supportive groups that build communication and coping skills without generating emotional distress. • Clients with high degrees of neuroticism will likely require a longer course of therapy to effect meaningful change in symptoms and functioning. We return now to our important question: Given ideal circumstances—a large number of client applicants and a wealth of information by which we can predict behavior—how then to compose the therapy group? There is no doubt that composition affects the character and process of the group, but the actual mechanism of influence has eluded full clarification.108 At the same time, it is clear that composition is not equivalent to destiny. It is instructive to keep in mind that the therapist’s skill can offset problematic and challenging relational styles among clients.109 We have had the opportunity to study the conception, birth, and development of more than 350 therapy groups—our own and our students’—and have been struck repeatedly by the fact that some groups seem to jell immediately, some come together more slowly, and others founder painfully or fail entirely. It also seems clear that the jelling and success of a group is only partly related to the competence or efforts of the therapist or to the number of “good” members in the group. To a degree, the critical variable is some as yet unclear blending of the members. A clinical experience many years ago vividly crystallized this conclusion for me (IY). I was scheduled to lead a six-month experiential group of clinical psychology interns, all at the same level of training and approximately the same age. At the first meeting, over twenty participants appeared—too many for one group—and I decided to split them into two groups. I asked the participants simply to move in random fashion around the room and talk to one another and, after five minutes, to form two equal-sized groups. Thereafter, each group met for ninety minutes, one group immediately following the other. Although the members of the two groups had much in common, it was

assumed an extraordinarily dependent posture. In the first group meeting, I arrived on crutches with my leg in a cast because I had injured my knee in an accident a couple of days earlier. Yet the group made no inquiry about my condition. Nor did they themselves arrange the chairs in a circle. (Remember that all were mental health professionals, and most had led therapy groups!) They asked my permission for such mundane acts as opening the window and closing the door. Most of the group life was spent analyzing my aloofness and coldness and their fear of me. In the other group, I was only halfway through the door before several members asked, “Hey, what happened to your leg?” The group moved immediately into hard work, and each of the members used his or her professional skills in a constructive manner. In this group I often felt redundant to the work and occasionally inquired about the members’ disregard of me. This “tale of two groups” illustrates how the makeup and composition of groups dramatically influence the character of the subsequent group work. If these groups had been ongoing rather than time limited, the different environments they created might eventually have made little difference in the beneficial effect each group had on its members. In the short run, however, the members of the first group felt more tense, more deskilled, and more restricted. Had it been a therapy group, some members of this group might have felt so dissatisfied that they would have dropped out of the group. Another pertinent narrative occurred in a large encounter group study.110 Two short-term groups were randomly composed but had an absolutely identical leader: a tape recording that provided instructions about how to proceed at each meeting. Hence, any variance in group outcome could not be attributed to effects of leadership. Within a few meetings, two very different cultures emerged: one group was obedient and subordinate whereas the other group was irreverent. The members of the second group mocked the tape’s instructions and nicknamed the taped voice “George.” Not only did the two groups evolve different cultures, but they had very different outcomes. At the end of the thirty-hour group experience (ten meetings), the irreverent (less dependent) group had an appreciably better outcome. HOMOGENEITY OR HETEROGENEITY? It is generally accepted clinical wisdom that intensive interactional therapy groups with the ambitious goal of deep interpersonal learning and change are more effective if their members are homogeneous in ego strength and the capacity to tolerate strong emotions, but heterogeneous in areas of conflict and interpersonal concerns.111 Homogeneous groups, on the other hand, have many advantages if the therapist wishes to offer support for a shared problem or to help clients rapidly develop skills needed for symptomatic relief.112 Such groups jell more quickly, become more cohesive, offer more immediate support to group members, are better attended, have less conflict, and provide more rapid relief of symptoms. Homogeneous groups can be tailored for specific kinds of difficulties that would preclude an interactional group—for example, a skill-building group for individuals on the autism spectrum with Level 1 difficulties, many of whom may

however, composition is not irrelevant. A seemingly homogeneous group for men with HIV, clients with Parkinson’s, or women with breast cancer will be strongly affected by the stage of illness of the members. An individual with advanced disease may ignite the other members’ greatest fears and lead to members’ disengagement or withdrawal.114 Even in highly specialized, manual-guided group therapies, such as groups for individuals dealing with a genetic predisposition to developing breast or colorectal cancer, the degree of member openness and capacity to care for one another will affect the group’s work.115 The issue becomes further clouded when we ask, “Homogeneous for what?” Age? Sexual orientation? Symptoms? Ethnoracial identity? Gender? Life developmental stage? Education? Socioeconomic status? Psychiatric diagnoses? Which of these variables are the critical ones? Is a group composed of women with bulimia, university students with social anxiety, or seniors with depression homogeneous because of the shared symptom, or heterogeneous because of the wide range of personality traits of the members? It is essential for the group leader to stay alert to these potential sources of difference and keep the uniqueness of each group member in mind. Homogeneous groups are most effective when the group leader does not homogenize the group members. Similarly, when we look at utilizing member heterogeneity to maximize interpersonal learning, we must avoid the hazard of creating an isolate or marginalizing an individual. S. H. Foulkes and E. J. Anthony, influential group analysts, suggested blending diagnoses and disturbances to form a therapeutically effective group.116 Consider the age variable: If there is one seventy-year-old member in a group of young adults, that individual may choose (or be forced) to personify the older generation. He or she may be stereotyped as the “transferential parent” and not seen as an authentic individual. A similar process may occur in an adult group with a lone late adolescent who assumes the unruly teenager role. Yet there are also advantages to having a wide age spread in a group. Most of our ambulatory groups have members ranging in age from twenty-five to eighty. Through working out their relationships with other members, they come to understand their past, present, and future relationships with a wider range of significant people: parents, peers, and children. The interaction between a seventy-five-year-old man working at repairing his relationship with his estranged daughter can be powerfully informed by a forty-year-old group member reconciling her relationship with her elderly, dying father. At the same time, it is important that members do not get locked into specific roles, whether they are roles they pursue or that the group projects onto them.117 We want the group to be a social microcosm, but one that is flexible rather than rigid. Ethnoracial, Cultural, and Gender Diversity Contemporary group leaders must pay great attention to group members’ sexual orientation, gender identity, cultural background, and ethnoracial factors. Our therapy groups should mirror our society and should model openness and acceptance to enhance in-depth exploration into members’ personal identities and desires.118 Group members from minority and racialized backgrounds will need

stereotypes. The group participants need to be alert to the risks of micro-aggressions—inadvertent or intentional slights and indignities rooted in societal bias and privilege. Therapists must be open to learning about each client’s personal sense of self in terms of sexual orientation identity and in ethnoracial and cultural terms.119 At times, some clients may actively avoid groups with members from their own ethnocultural background because of feelings of shame and fear of exposure within their larger community. At other times, as in the case of group therapy for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a powerful shared experience and the accompanying psychological sequelae can outweigh ethnoracial factors.120 What about gender and group composition? Some authors advocate single-gender groups. The group therapy research, however, does not strongly support this approach. Mixed-gender groups are clearly effective, though all-female groups may be indicated when issues of sexual abuse and shame are prominent.121 Gender dynamics and the intertwining of the political and the personal will likely emerge in mixed-gender groups, mirroring our contemporary environment. Therapy groups may reinforce gender stereotypes or challenge them, particularly around the dynamics of power, vulnerability, and tenderness.122 Women in general carry more positive attitudes toward group therapy than men.123 The presence of women in groups benefits the male group members. Men in all-male groups are often less intimate and more competitive than they are in mixed-gender groups, where they tend to be more self-disclosing and less aggressive. Unfortunately, the benefit of gender heterogeneity does not always accrue to the women in these groups: women in mixed-gender groups may become less active and more deferential to the male participants. Mixed-gender groups consisting of only one or two men and several women may result in the men feeling peripheral, marginalized, and isolated.124 A discussion of gender and group composition also reminds us that for many clients seeking group therapy, gender identity is nonbinary. Both trans and gender-nonconforming individuals need assurance that a safe space will exist in their groups for disclosure, exploration, and interaction. It is essential that their identity and preferred ways of being addressed are respected and honored in the group.125 GENERAL CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS Groups do better if some members are advocates of constructive group norms. Placing one or two “veterans” of group therapy into a new group may pay large dividends. Leaders must attend to the fit and the timing of entry of a new member. A challenging, controlling, and devaluing client may very much need group therapy but may overwhelm a group early in its development. Such a client is more likely to succeed in a mature and cohesive group.126 We can sometimes predict that clients will fit poorly with a particular group at a particular time because of the likelihood that they will assume an unhealthy role in it. Consider this clinical illustration:

personality difficulties, was evaluated for group therapy. She was professionally successful but interpersonally isolated, and experienced chronic dysthymia that was only partially ameliorated with antidepressants. When I (IY) saw her for a pregroup consultation, I experienced her as brittle, explosive, highly demanding, and devaluing of others. In many ways, Alicia’s difficulties echoed those of another woman, Lisa, who had just quit the group (thereby creating the opening for which Alicia was being evaluated). Lisa’s intense, domineering need to be at the center of the group, coupled with an exquisite vulnerability to feedback, had paralyzed the group members, and her departure had been met with clear relief by all. At another time, this group and Alicia could have been a constructive fit. So soon after Lisa’s departure, however, it was very likely that Alicia’s characteristic style of relating would trigger strong responses of “here we go again,” reawakening feelings that group members had just painfully processed. An alternative group for Alicia was recommended. << One additional clinical observation: As a supervisor and researcher, I (IY) had an opportunity to closely study an entire thirty-month course of an outpatient clinic group led by two effective psychiatric residents. The group was remarkably homogeneous in composition and consisted of seven members, all in their twenties. Six of them were identified at the time as having schizoid personality disorder. To observers the group seemed remarkably dull, slow, and plodding. And yet attendance was nearly perfect, and group cohesiveness extraordinarily high.127 Thorough evaluations of clinical progress were available at the end of one year and again at thirty months. The members of this group (both the original members and the replacements) did extraordinarily well and underwent both substantial characterological changes and significant symptomatic remission. This apparently homogeneous group, contrary to the clinical dictum, did not remain at a superficial level and effected significant personality changes in its members. Although the interaction seemed lumbering to the therapists and researchers, it did not to the participants. None of them had ever had intimate relationships, and many of their disclosures, though objectively unremarkable, were subjectively exciting first-time disclosures for them. What emerges from this illustration is the recognition that many so-called homogeneous groups remain superficial not because of homogeneity, but because of the psychological mindset of the group leaders and the restricted group culture they fashion. Therapists leading a group of individuals with a common symptom or life situation must be careful not to convey implicit messages that generate group norms of restriction, a search only for similarities, and discouragement of self-disclosure and differentiation. Norms, as we elaborated in Chapter 5, once set into motion, may become self-perpetuating and difficult to change. One other perspective on composition comes from the rare, but impossible-to-forget, experience of asking a client to leave a group. In our experience, over many years, many groups, and thousands of clients, this situation has come up only a handful of times. Invariably, the clients were asked to leave their group because their participation made the group unworkable. They made the group unsafe for others by attacking, shaming, and devaluing group members. They refused to be accountable for their impact, despite much feedback, and would

approach, stating, “I call it the way I see it and people are just being babies here.” There was no spirit of collaboration, and every therapeutic tactic employed was met with fierce resistance. The groups affected were literally withering over time, and the group leaders had no choice but to ask the offensive members to leave. In such instances the therapist still has clinical responsibility for the client and should offer a referral for further individual therapy in which the client may be able to process the events in the group. SUMMARY: GROUP COMPOSITION In our examination of the research and clinical literature about client selection and group composition, we are on much surer footing when discussing the selection of clients for group therapy than when discussing the composition of the therapy group. However, though there is no certainty about the best composition of groups, there are some instructive principles to guide us. Our approach to composition is informed by our understanding of the group’s tasks: First, we wish to capitalize fully on the group as a social microcosm—a miniature social universe in which members understand and improve their interactions with a variety of other individuals. Hence the group should resemble the real social universe, composed of members with varying interpersonal styles, conflicts, gender, occupations, cultural and ethnoracial backgrounds, ages, and socioeconomic and educational levels. Yet the group should be sufficiently homogeneous for its members to engage the demands of group therapy. It is a delicate balance. If the challenges are too great, and the staying forces (the attraction to the group) too small, the individual does not change but instead physically or psychologically leaves the group. On the other hand, if the challenge is too small, no learning occurs, members will collude, and exploration will be inhibited. Second, the group must be able to respond to members’ needs both for emotional support and for constructive challenge. On the basis of our current knowledge, therefore, we propose that cohesiveness be the primary guideline in the composition of therapy groups. Cohesive groups with higher engagement generally produce better clinical outcomes than noncohesive groups.128 Hence, group therapists must select clients with the lowest likelihood of premature termination. Individuals with a high likelihood of being irreconcilably incompatible with the prevailing group ethos and culture should not be included in the group. It bears repeating that group cohesiveness is not synonymous with group comfort or ease. Quite the contrary: it is only in a cohesive group that conflict can be tolerated and transformed into productive work. Thus, we advocate forming a group by accepting, within limits, the first suitable seven or eight candidates screened and deemed to be good group therapy candidates. We suggest having an equal number of men and women and a wide range of ages, interactional styles, and expected levels of activity and engagement. The therapist’s paramount task is to create a group that coheres. There is no question that composition radically affects a group’s character. Yet, given the current state of our knowledge and clinical practice, there is no justification for

Fleepit Digital © 2021