Theories Occupational therapy’s distinct value is to improve health and quality of life through participation and engagement in meaningful, necessary, and familiar activities of everyday life (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2018). In keeping with the WHO International Classification of Function Disability Functioning, (WHO, 2001), occupational therapy promotes health by focusing on the individual, environment, and occupations through a top-down approach. The advancement of research in occupational science endorses the move away from a focus on individual skill development promoted by other professions to a holistic approach of development focusing on meaningful engagement in occupations within the context in which the child participates. Intervention focusing on occupation with secondary improvement of underlying skills requires a shift in thinking for many occupational therapists (Humphry, 2005). This renewed holistic developmental focus allows occupational therapists to promote occupational performance for children of all ages, cultures, and abilities. Occupational science research can be used to understand the occupational development of children by exploring the: 1. occupational perspective of health (OPH), including doing, being, becoming, and belonging; 2. transactional relationship between the child and the contexts in which they participate, and 3. bioecological view of development, including the relationships with child, caregivers, family, community, and within geopolitical contexts. OPH: Doing, Being, Becoming, Belonging The Occupational Perspective of Health (OPH) developed by Wilcock (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015) provides a framework for guiding the developmental growth of children in a holistic way. According to the OPH, occupational development and competence occurs through a process of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. The four constructs have been defined, illustrated, and expanded to provide an integration of the theory for clinical application (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015; Hitch, Pepin, & Stagni i, 2014). In the first construct of the OPH, doing, children may engage actively or passively in the performance of occupations they need to do, want to do, or are expected to do. This can promote the child’s identity as a dynamic participant in the world (King et al., 2003). The being stage of occupation has been interpreted in three different ways in the literature. The first and original idea of being requires time for rest, relaxation, and space to reflect and just be. Being can also mean reflection on how one feels about participation in an occupation from a psychological or spiritual sense, and the understanding and advocacy of the self as an occupational being. The adoption of roles is important in understanding being, for example being a student, being a musician, or being a helper. This construct allows discovery of the inner essence of the child or adolescent despite or because of physical, mental, environmental, or social conditions. The process of being can be elicited through participation in art activities, mindful activities such as yoga and meditation, and through reflection in journals or drawing regarding self as an occupational being (Gunnarssson, Peterson, Leufstadius, Jansson, & Eklund, 2010; Hocking, 2009). Becoming can be understood as development and transformation into an occupational being. “Becoming aims for a person’s highest potential, the best possible outcome” (Hitch et al., 2014). Through participating in new experiences, opportunities, and challenges, children may be able to achieve goals that they set for themselves. In becoming, the child develops into an active participant by doing self-selected occupations in which they choose to participate. Wiseman, Davis, and Polatajko (2005) found that children engaged in occupations for self-improvement and gaining competence, and sustained participation through selfmotivation. Becoming for children often involves other people for assistance, affirmation, and support. Parent’s views, expectations, and values affected which occupations students participated in and had a large effect on students’ success (Loughlan-Presnal & Bierman, 2017; Wiseman, Davis, & Polatajko, 2005). The fourth construct, belonging, is the phase that has the most developmental impact for long-term health and wellness. A sense of belonging is described as “being part of, a member of, a constituent of, associated with, connected with, included in something, feeling right, and fi ing in” (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015, p. 137). Active engagement in occupations within the contexts that children participate provide opportunities for social, educational, and cultural inclusion. Physical and social inclusion is the first step in the process of active engagement and participation. Through the process of doing, being, and becoming an occupational individual, the child is motivated and empowered through the selection of the occupations they want to perform and belonging to the social communities they prefer. 164

grouped and analyzed based on the client, occupations, and contexts in which a child is situated. For example, students with severe physical disabilities may not be able to “do” certain occupations such as write independently with a pencil, but this does not limit their becoming a story writer with the use of adaptive technology, or the sense of belonging in the writing center in the classroom. Occupational therapists help children and adolescents participate in meaningful occupations to develop an identity as an occupational being leading to belonging in the social, cultural, physical, virtual, and temporal contexts they choose. Transactional Relationship Between Child and Contexts Occupational performance, competence, and identity (occupational identity) as an occupational being are influenced by the contextual environments in which a child/adolescent participates. The abilities to do, be, become, and belong are embedded in social participation and engagement and are an important aspect of children’s daily lives. A child’s occupations are always situated within a place. A place is an environment that “simultaneously serves a function, motivates a person’s participation[,] and is subject to real time meaning and significance” (Petrenchick & King, 2013, p. 78). A child’s actions and behaviors must be understood as coherent occupations within specific contexts. Hocking (2009) defines this process as occupational forms. Occupational forms, “elicit, guide, and structure occupational performance…This includes both the immediate physical environment in which the performance takes place and it[]s sociocultural reality. The form influences what is done” (Hocking, 2009, p. 141). Dickie, Cutchin, and Humphry (2006) proposed a transactional view of occupation based on a relationship between the person and environment instead of viewing occupational performance as separate units of the individual, environment, and occupation. By defining the mutual, reciprocal, multifaceted interfaces that occur between an individual and the contexts in which they live, the developmental growth and trajectory of a child can be examined. Children develop occupations through participation in family activities and cultural practices initially and expand to participation in community contexts outside of the home as they grow. These contexts are placed within a geopolitical context of societal norms that affect the behavior and occupations of families and children (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015; Silcock, Hocking, & Payne, 2014). See Figs. 4.11A and B that show children engaged in occupations within different contexts. Physical, psychological, social-emotional, or mental trauma may interfere with the progression and sequence, causing a “gap” in the child’s development. Llorens (1997, 1982) hypothesized, as a child participates in the family’s cultural, social, and temporal practices, the child learns occupations and performance skills that enable him or her to become a full participant in the home and extended community. Child-oriented environments are physically safe, emotionally secure, and psychologically enabling, allowing children and adolescents the opportunity to explore and gain competencies and a positive sense of self. Bioecological Model of Development The transactional view of occupational therapy can be illustrated through the bioecological model of development, established and revised by Bronfenbrenner (Brofenbrenner, 1979; Brofenbrenner & Morris, 1998). In this model, child development is situated as a reciprocal interrelationship between the characteristics of the child and the environments in which they engage. As seen in Fig. 4.12 the bioecological model emphasizes the importance of the physical, social, cultural, virtual, and temporal context on child development and explains the reciprocal interactions among and between the child, family, community, and geopolitical contexts on a child’s occupational participation and performance. 165

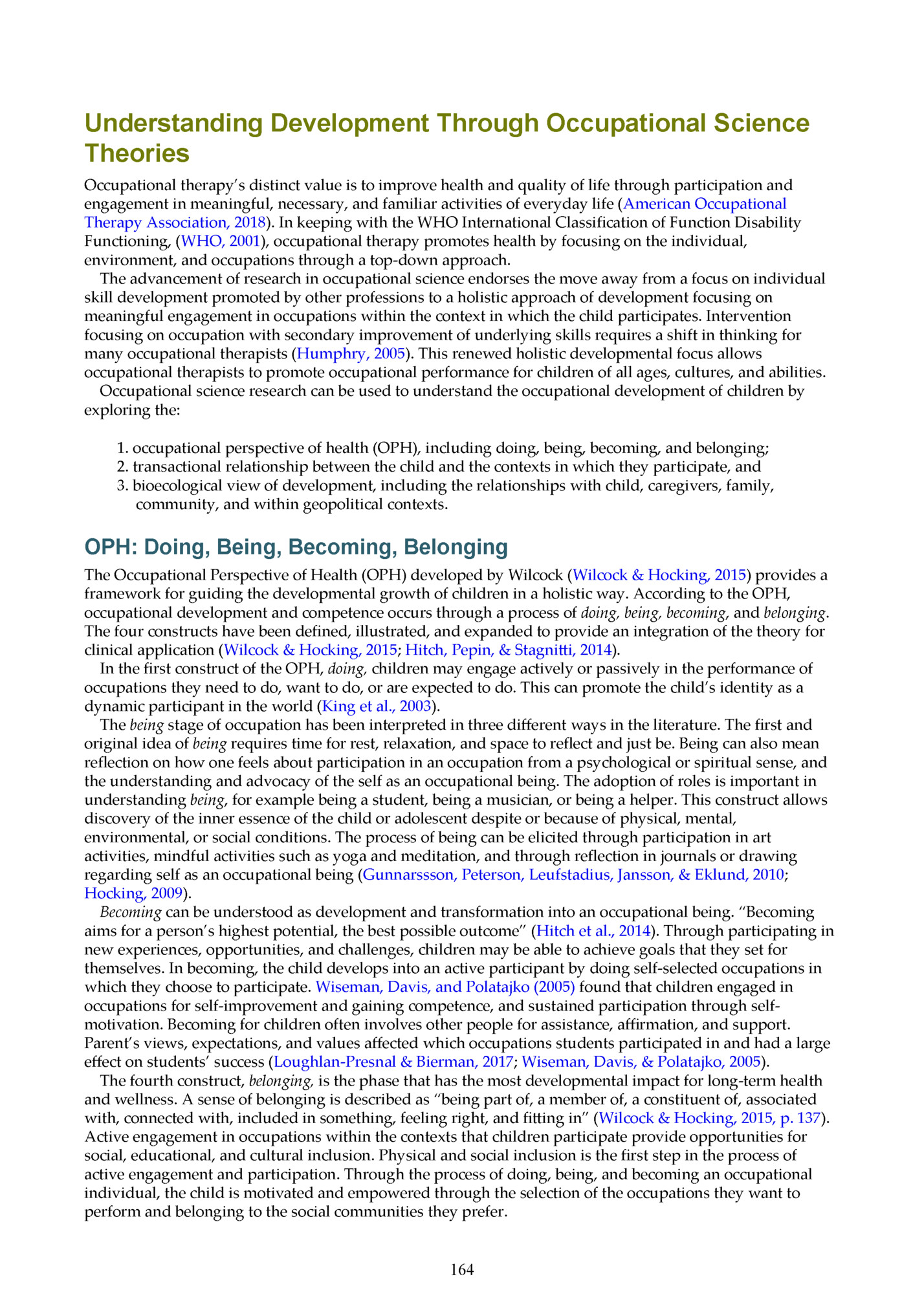

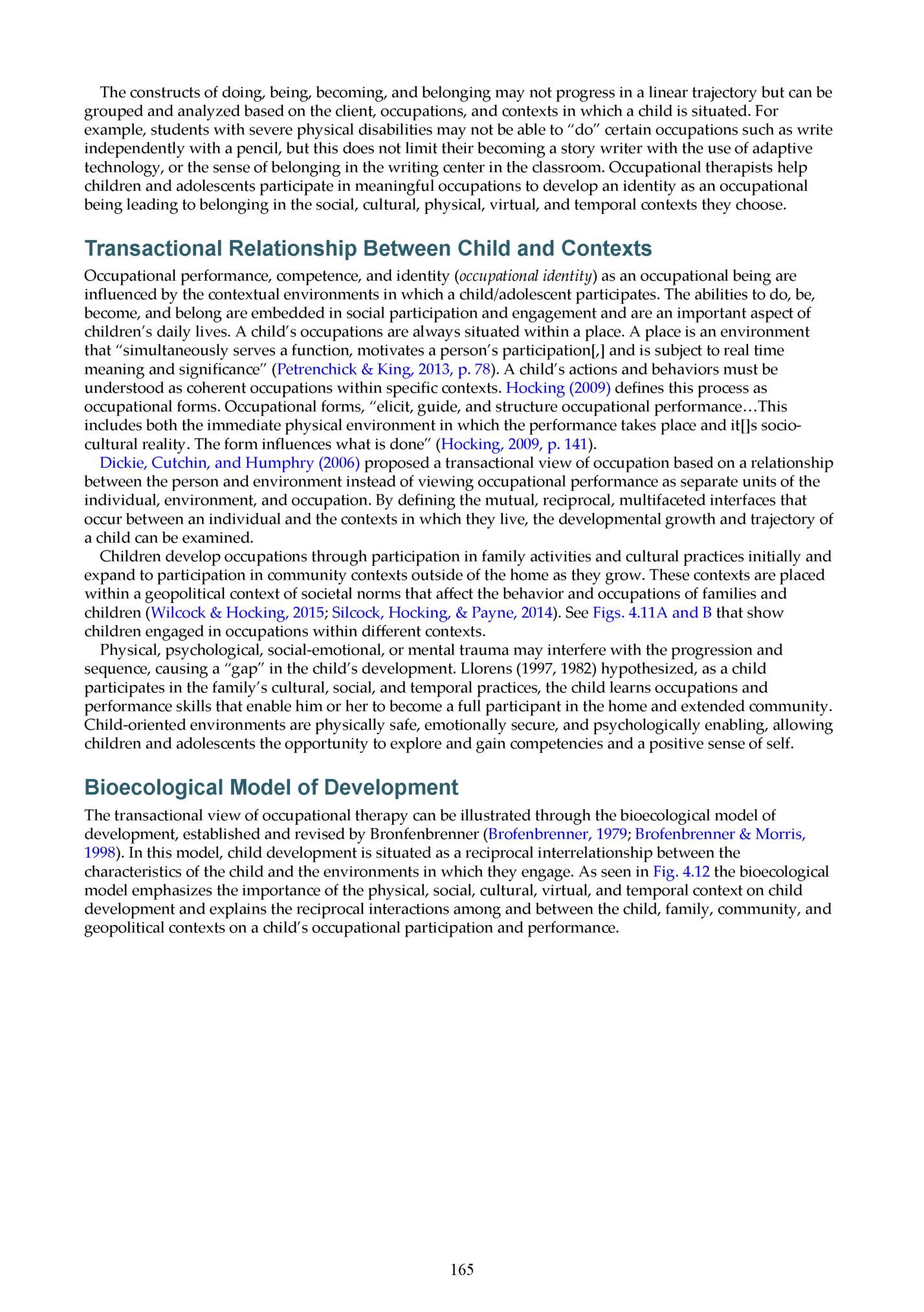

language other than English and are placed in special education. Occupational alienation is a ‘‘prolonged experience of disconnectedness, isolation, emptiness, lack of a sense of identity, a limited or confined expression of spirit, or a sense of meaninglessness’’ (Townsend & Wilcock, 2004, p. 80). An example of occupational alienation are children who have been detained in any way, such as in foster care, immigration centers, or criminal institutions for juveniles. Box 4.3 Effects of Social Media on Teens 13–19 Years of Age Positive Effect (31%) Connect you with family and friends Negative Effect (24%) It can lead to bullying or rumor spreading (or being bullied and the victim of rumors) It is easier to get news and information It can harm relationships, lack of in-person contact You can meet others with same interests Provides an unrealistic view of others’ relationships Keeps you entertained and upbeat Causes distraction and even addiction to the media Supports self-expression Peer pressure You can get support from others Causes mental health disruptions You can learn new things Adapted from: Pew Research Center (2018). Internet and technology: Teens, social media, and technology. Integrating the Bioecological Model and Occupational Science As a transactional model, the bioecological model illustrates the occupational science theory of doing, being, becoming, and belonging and demonstrates how transactions within and among contexts (e.g., physical, social, political) support or hinder the child’s occupational development. For example, the environment may support and interact with the child’s actions, compelling the child to adapt or accommodate. Conversely, a context may have limits and challenges, such as an inaccessible playground for a child in a wheelchair. Through adaptation and accommodation for the child’s needs (e.g., learning disability, physical disability), family needs, physical environment, and access to financial and community resources, the child is likely to achieve occupational participation, competence, and the developmental maturation necessary for generalization of occupational skill, continued learning, and physical and mental wellness. Case Example 4.3 illustrates the influence of contextual factors. FIG. 4.19 Bilingual children scan two cultures: the American culture of school and neighborhood and the culture of their family. This child bridges cultures through an internet channel teaching English to other Brazilian children. The role of the occupational therapist in this transactional model is to promote occupational justice through adapting and transforming environments to support occupational performance. As advocates for children, occupational therapists work as change agents to ensure physical, social, and cultural accessibility appropriate for children with a wide range of abilities for them to do, be, become, and belong. Occupations and Co-Occupations for Transformational Development 175

inexperience in navigating environments necessitates the child’s social engagement with others. Cooccupations are integral to child development and initially consists of caretakers participating in the same occupation as the child to help the child develop, such as feeding an infant, reading aloud at bedtime, or cooking a meal (Humphrey & Thigpen, 1998; Zemke & Clark, 2006). Co-occupation is the performance of occupation “in a mutually responsive, interconnected manner that requires aspects of shared physicality, shared emotionality, and shared intentionality” (Davel-Pickens & Pizur-Barnekow, 2009, pp.151). Fig. 4.20 illustrates Co-occupations between a child and grandparent. The nurturing of co-occupational relationships is important for occupational development. Utilizing therapeutic use of self, occupational therapists partner with children and the adults working with them (e.g., caregivers, daycare providers, teachers, religious educators, and scout leaders) to develop intervention that is meaningful and motivating to the child and leads to self-efficacy (Humphry, 2009; Taylor, 2017). Scaffolding, guidance, cueing, prompting, and reinforcement by an occupational therapist can assist the child in occupational performance. This direct involvement from a caregiver or other adult can facilitate performance at a higher level. In the case of a child with disabilities, a more intensive level of direct support and scaffolding may be necessary through cooccupation. Case Example 4.3 Maria is a 4-year-old child diagnosed with cerebral palsy who uses a wheelchair for mobility. She lives with her parents, grandmother, and four older siblings (two boys and two girls) in a third-floor walk-up apartment in a metropolitan city. Maria is carried up the stairs by her father or mother. Since it is difficult to carry her up and down the stairs, Maria does not get out as often as her family would like for community activities, although they try to get out once a day. During the week she a ends an early intervention program, where she gets occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT), and speech therapy. She also enjoys socializing with her siblings and relatives at home. Emma, a 4-year-old girl with cerebral palsy, also a wheelchair for mobility. She lives in a one-story farmhouse with her grandparents in a rural community. She has access to leisure activities (a large backyard) and chores (she helps with the animals and the garden). Emma does not socialize with neighbors, peers, or community members. She a ends an early intervention program during the week, where she gets OT, PT, and speech therapy. While Maria and Emma experience similar diagnoses and may have similar performance capacities, their development is affected by the contexts in which they live. The occupational therapy intervention sessions will reflect their individual needs and the contexts in which they live. Maria benefits from the socialization she gets with her siblings and relatives, resources of the city environment, and accessibility of adapted spaces (accessible parks nearby). However, her home se ing is not wheelchair accessible, which prevents her from engaging in some desired occupations. She is not independent in ge ing into her home which may influence her self-efficacy. Emma, on the other hand, has natural space readily available to her but has limited opportunity to socialize with same-aged peers. She may require adaptations at home so that she can complete chores and engage in play outside (e.g., paths or ramps, adapted swings). Emma spends time with adults and may not have established important peer relationships needed to establish a sense of autonomy for self-efficacy. These cases illustrate the contextual factors that transact with the child to determine occupational therapy intervention. The occupational therapist also works with the families to understand the technology needs of each child. Both children are receiving services under IDEA (2012) so they may qualify for assistive technology. They may also have medical insurance to provide additional services or equipment. Occupational Performance Milestones: Opportunties for Intervention Developmental milestones are skills children achieve that may inform intervention planning. The ages in which children achieve developmental milestones can vary and many factors and environmental contexts influence a child’s performance. Developmental milestones therefore, are considered guides and not fixed age norms. Usual occupations children perform in various stages and the performance skills required are reviewed in the next pages. See back of chapter for appendices of developmental milestones in various skills and occupations. Understanding the sequence of development provides information regarding which skills are more readily achieved and may inform intervention planning. However, occupational therapists understand that not all children follow the sequence and that age expectations vary. Furthermore, many factors and environmental contexts influence a child’s performance. Developmental milestones are considered guides and not fixed age norms. 176

Observational Assessment and Activity Analysis Susan L. Spi er GUIDING QUESTIONS 1. What is the relationship of activity analysis to pediatric occupational therapy? 2. What are the similarities and differences between the two types of activity analysis? 3. How does a theoretical model or frame of reference guide activity observation and analysis? 4. What are the specific contributions of activity observations and analysis to pediatric evaluation? 5. How are activity observations and analysis performed in pediatric occupational therapy? 6. How are the activity analysis and observational assessment findings synthesized to guide pediatric intervention? KEY TERMS Activity analysis Activity match Activity synthesis Grading Modification Occupational performance Activity observations and analysis are essential tools for assessing and supporting occupational performance for children and adolescents. Embedded in the profession’s historical and philosophical focus on occupations and everyday activities, they continue to be pragmatically necessary for the everyday work of pediatric occupational therapy. They are the essence of what occupational therapists do and are integrated across diverse practice areas and theoretical frameworks. Clinical use of activity observations and analysis involves extensive therapeutic reasoning and mindful practice to develop skill and expertise. This chapter first describes activity observation and analysis, including the distinct history and role of activity analysis in occupational therapy, the types of activity analyses, and the relationship to frames of reference. Next, the chapter explains their important contribution to the evaluation process and demonstrates how to utilize activity observations and analysis to assess occupational performance in children and adolescents. Finally, the chapter illustrates how occupational therapists working with children and youth synthesize these results for intervention. Activity Observation and Analysis Activity analysis is at the essence of pediatric occupational therapy practice and professional identity. The concept of activity analysis dates to 1911 when Frederick Taylor and Frank Gilbreth applied the study and analysis of motion as a scientific approach to maximize worker productivity in industry (Creighton, 1992). In 1917, this approach was presented at the founding occupational therapy conference. Occupational therapists quickly adopted and utilized this tool to identify systematically what motions, tools, or methods could be adapted to improve physical function or compensate for deficits (i.e., Kidner, 1930). By the following decade, 248

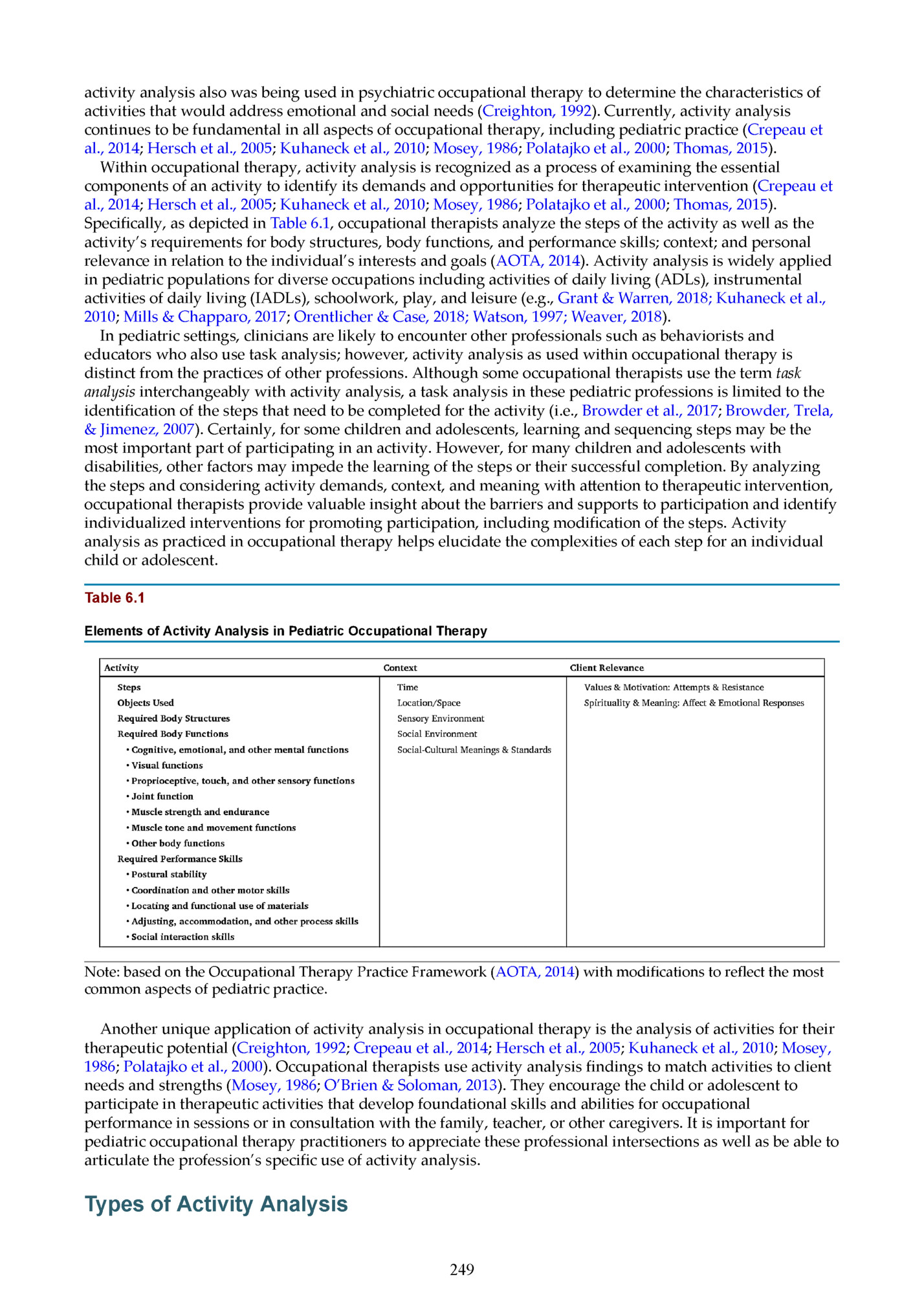

activities that would address emotional and social needs (Creighton, 1992). Currently, activity analysis continues to be fundamental in all aspects of occupational therapy, including pediatric practice (Crepeau et al., 2014; Hersch et al., 2005; Kuhaneck et al., 2010; Mosey, 1986; Polatajko et al., 2000; Thomas, 2015). Within occupational therapy, activity analysis is recognized as a process of examining the essential components of an activity to identify its demands and opportunities for therapeutic intervention (Crepeau et al., 2014; Hersch et al., 2005; Kuhaneck et al., 2010; Mosey, 1986; Polatajko et al., 2000; Thomas, 2015). Specifically, as depicted in Table 6.1, occupational therapists analyze the steps of the activity as well as the activity’s requirements for body structures, body functions, and performance skills; context; and personal relevance in relation to the individual’s interests and goals (AOTA, 2014). Activity analysis is widely applied in pediatric populations for diverse occupations including activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), schoolwork, play, and leisure (e.g., Grant & Warren, 2018; Kuhaneck et al., 2010; Mills & Chapparo, 2017; Orentlicher & Case, 2018; Watson, 1997; Weaver, 2018). In pediatric se ings, clinicians are likely to encounter other professionals such as behaviorists and educators who also use task analysis; however, activity analysis as used within occupational therapy is distinct from the practices of other professions. Although some occupational therapists use the term task analysis interchangeably with activity analysis, a task analysis in these pediatric professions is limited to the identification of the steps that need to be completed for the activity (i.e., Browder et al., 2017; Browder, Trela, & Jimenez, 2007). Certainly, for some children and adolescents, learning and sequencing steps may be the most important part of participating in an activity. However, for many children and adolescents with disabilities, other factors may impede the learning of the steps or their successful completion. By analyzing the steps and considering activity demands, context, and meaning with a ention to therapeutic intervention, occupational therapists provide valuable insight about the barriers and supports to participation and identify individualized interventions for promoting participation, including modification of the steps. Activity analysis as practiced in occupational therapy helps elucidate the complexities of each step for an individual child or adolescent. Table 6.1 Elements of Activity Analysis in Pediatric Occupational Therapy Note: based on the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (AOTA, 2014) with modifications to reflect the most common aspects of pediatric practice. Another unique application of activity analysis in occupational therapy is the analysis of activities for their therapeutic potential (Creighton, 1992; Crepeau et al., 2014; Hersch et al., 2005; Kuhaneck et al., 2010; Mosey, 1986; Polatajko et al., 2000). Occupational therapists use activity analysis findings to match activities to client needs and strengths (Mosey, 1986; O’Brien & Soloman, 2013). They encourage the child or adolescent to participate in therapeutic activities that develop foundational skills and abilities for occupational performance in sessions or in consultation with the family, teacher, or other caregivers. It is important for pediatric occupational therapy practitioners to appreciate these professional intersections as well as be able to articulate the profession’s specific use of activity analysis. Types of Activity Analysis 249

Fleepit Digital © 2021