Thick (liquids) Uniform texture Stays together (will not break up in the mouth) Easy to remove and suck Contraindicated Foods Multiple textures and consistencies (e.g., tacos, vegetable soup, stews, salads) Sticky (e.g., peanut bu er) Greasy (e.g., fried foods) Tough (e.g., red meat, processed meats, diced fruit) Fibrous and stringy (e.g., celery, citrus fruits, raw vegetables) Skins (raw fruits, peanuts) Spicy (pepper and horseradish) Seeds and nuts (plain or in breads and cakes) Thin liquids (e.g., water, broth, coffee, tea, apple juice) Quickly liquefying (e.g., Jell-O, ice cream, and watermelon) Foods that break up in the mouth (e.g., some cookies and flaky pastries) Hard, crunchy (e.g., carrots) With free-flowing liquid from an open cup or nonvalved spouted cup, children should be in an upright position to encourage bolus formation in the mouth, without the influence of gravity on liquid flow into the pharyngeal space. Children may also benefit from thickened liquids when first learning to drink from a cup to compensate for decreased oral control or pharyngeal swallowing skills. External jaw support can be provided by the occupational therapist whose index finger is placed below the mandible and the thumb is placed on the anterior chin. Providing jaw support while si ing beside the child with the arm around the back of the child’s neck may allow the occupational therapist to provide additional stability for the child to maintain adequate head alignment (Fig. 10.10). Children often bite on the rim or spout of the cup to gain jaw stability. They also may push the cup into the corners of their lips or rest their tongue on the rim of the cup for additional stability sensory input (Morris, 2000). These pa erns should decrease over time as the child becomes more skilled in managing liquids from a cup. Neuromuscular Interventions for Oral Motor Impairments A wide range of children demonstrate oral motor impairments that affect the development of feeding skills. Oral motor problems are seen frequently in children with global neuromuscular impairments caused by cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, prematurity, or genetic conditions such as Down syndrome (CooperBrown, 2008). Children without neuromuscular impairments may also demonstrate oral motor problems when they are delayed in transitioning from a bo le to a cup or from puréed foods to textured foods. Inexperience with normal feeding activities may contribute to oral motor weakness and coordination difficulties. Oral hypersensitivity may cause a child to retract the tongue into the mouth to avoid stimulation, contributing to maladaptive oral movement pa erns. Occupational therapists include oral motor activities within a comprehensive intervention plan to promote strength and coordination for the development of more advanced oral feeding skills. 398

Whenever possible, oral motor activities should include foods or flavors to incorporate taste receptors and facilitate the integration of sensory processing and motor skills for a functional response. Hypersensitive children may tolerate nonnutritive activities initially before they are able to accept the additional sensory input that food flavors provide. Jaw weakness can be seen in children with neuromuscular oral feeding difficulties. This weakness may contribute to an open-mouthed posture at rest, drooling, food loss during feeding, difficulty with chewing a variety of age-appropriate foods, or poor stabilization when drinking from a cup. Jaw weakness and instability may also affect lip closure for spoon-feeding and control during swallowing. Occupational therapists may facilitate jaw strength with a variety of nonnutritive or nutritive activities. Nonnutritive 399

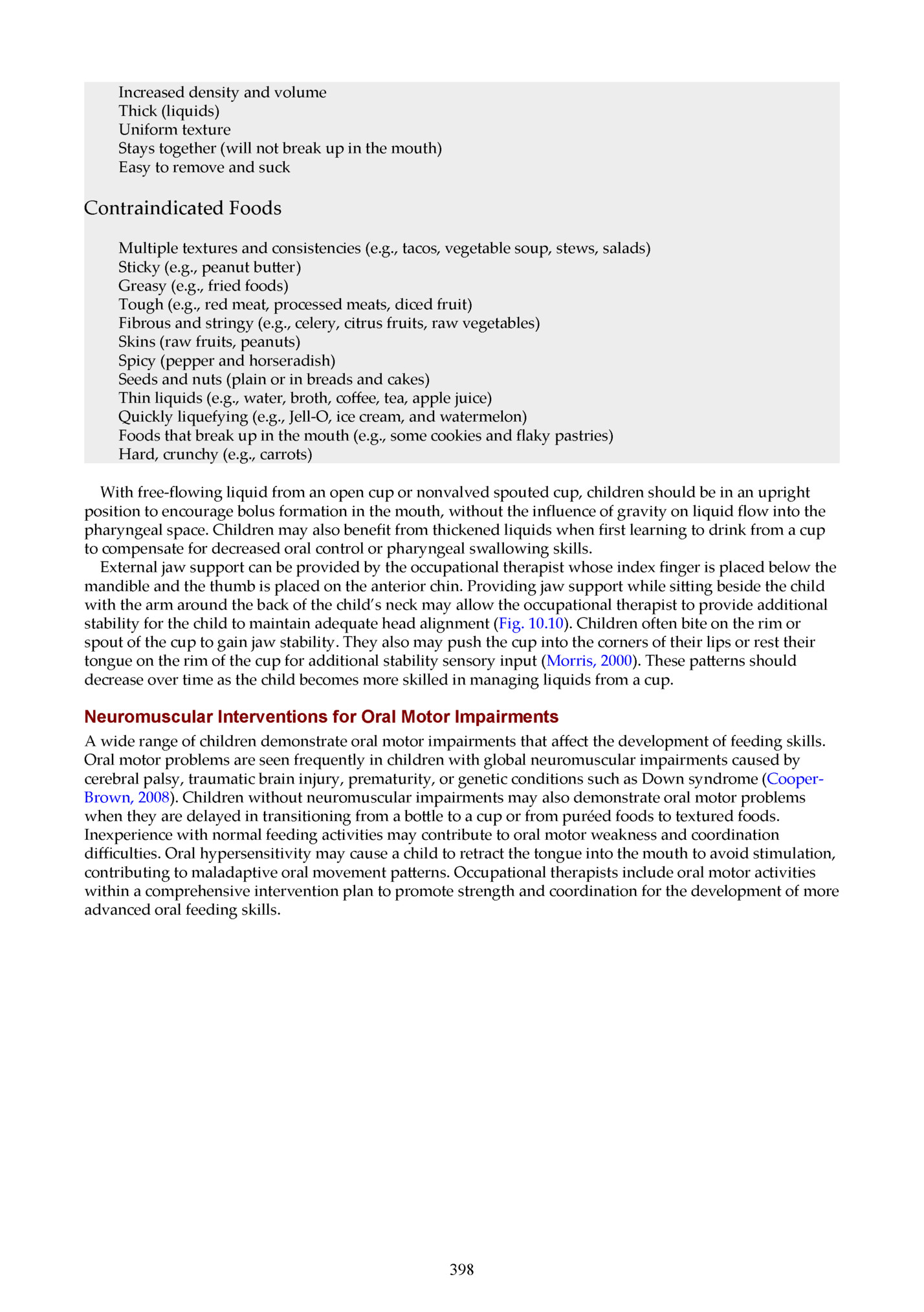

tubing before the introduction of food textures. Nutritive jaw strengthening activities may include biting or chewing on fruits or vegetables encased in a mesh pouch or progressive resistive activities with a variety of solid or chewy foods placed over the molar surfaces (Rosenfeld-Johnson, 2005). It is important to take into consideration the child’s oral motor chewing abilities as foods and food textures are introduced. Never offer foods, even for oral motor practice, which the child is unable to chew and swallow safely as it poses an unnecessary choking risk to the child. FIG. 10.11 Oral motor activities. Children with neuromuscular impairments may have strong pa erns of abnormal oral movement. The child may exhibit a tonic bite by biting down forcefully in response to a stimulus and demonstrate subsequent difficulty opening or relaxing the jaw. A strong tongue thrust movement pa ern may also be present, in which the tongue forcefully protrudes beyond the border of the lips during oral feeding activities. A well-supported and slightly flexed head position may reduce these abnormal movement pa erns. Children with tongue thrust may also benefit from oral motor activities to facilitate tongue lateralization and placement of the spoon or food bolus to the sides of the mouth, rather than at midline (Fig. 10.11) (Beckman, 2000). Children may demonstrate immature forward-backward tongue movements during feeding, poor dissociation of the tongue from the jaw, and poor tongue lateralization to control textured food over the molar surfaces. Occupational therapists may engage the child in activities to facilitate tongue movements, such as encouraging the child to make silly faces in a mirror or lick lollipops, frosting, or whipped cream from the corners of the mouth or within the cheeks. Stimulating the sides of the tongue and inside the cheeks with a Nuk brush or oral motor tool may also encourage tongue lateralization. Problems affecting the lips and cheeks include abnormal tightness or weakness. A child may demonstrate lip or cheek retraction, making it difficult for the child to assume or sustain lip closure. Adequate lip closure and lip seal are needed to assist the child with oral food control and prevent anterior spillage during feeding. It is very difficult to swallow with retracted lips and cheeks because the lips seal the oral cavity to create pressure to propel the food bolus into the pharyngeal cavity. Slow perioral and intraoral cheek elongation can help promote lip closure before initiating functional activities with whistles or with spoon-feeding. Oral motor therapy is an important component of a global treatment approach for children with feeding problems (AOTA, 2008; Howe & Wang, 2013 ). A recent systematic review by Howe and Wang (2013) indicates that research evidence supports the use of oral motor and physiologic interventions for preterm infants, children with neuromuscular impairments, and children with oral structure abnormalities such as cleft palate. An important study evaluating oral motor intervention in children with cerebral palsy published by Gisel et al. (1995) remains relevant, reminding the occupational therapist that while these interventions may show improvement in some functional feeding activities, the research evidence is limited regarding improvements in nutrition anthropometrics and swallow function. 400

Transition From Nonoral Feeding to Oral Feeding Nonoral feeding with a gastrostomy, nasogastric tube, or other method is indicated when a child is unable to meet his or her nutrition or hydration needs by mouth. Nonoral feeding methods may be used when the child has dysphagia; complex heart, respiratory, or other medical conditions; or GI problems. Other children require nonoral feeding simply because they are unable to consume enough food or liquid by mouth for adequate growth and hydration. Inadequate nutrition or hydration can severely impact a child’s motor development, cognitive development, and health (Gisel, 1995). The placement of a gastrostomy tube or the use of other nonoral feeding methods can be a temporary or long-term measure to promote the child’s nutritional status and growth, depending on the child’s needs (Tarbell, 2002). When children receive nonoral feeding, they are at risk for oral motor and oral sensory impairments related to limited oral feeding experiences (Scarborough, 2006). Nasogastric and orogastric tubes may also create sensory distress for the child during placement of the tube. When these tubes are needed over a long period, they are typically reinserted or replaced at least once per month, causing further sensory distress to the child (Fig. 10.12). Occupational therapists may provide an intervention program to provide ongoing oral exploration activities and social engagement during nonoral feeding. The goals are to create positive social and oral exploration experiences daily and ultimately link these pleasurable experiences with the sensation of hunger satiation. If the child has a history of aspiration or if oral feeding is not medically safe, the child may suck on a pacifier or engage in mouth play with teethers, spoons, and toys during nonoral feeding. Occupational therapists and caregivers can engage in games that include touch and exploration around the face and mouth. Children may also benefit from games that encourage them to make different sounds with their mouth, give kisses, or blow whistles or bubbles. Whenever possible, occupational therapists should encourage families to treat tube feedings as mealtimes and to include their child in mealtime routines, such as si ing with the family at the table during feedings and oral play activities. When the child is ready to have nutritive stimulation, occupational therapists and caregivers can provide flavors or tastes of foods by dipping a finger, pacifier, spoon, or toy into juice, formula, or puréed foods. Children who receive nonoral feeding may have limited opportunities to experience typical feelings of hunger. This is especially true when children require nonoral feedings on a continuous schedule, across many hours during the day or overnight. Children who can tolerate more compressed bolus feedings may have more opportunities to experience hunger, which may increase the child’s motivation to consume some foods by mouth. As the child begins to advance oral intake skills, occupational therapists need to collaborate with physicians or dietitians who can determine appropriate schedule changes and reductions in nonoral nutrition. Children who have a tracheostomy often require nonoral feeding methods. The risk and complications of aspiration are significantly increased in a child with a tracheostomy because of the fragility of the respiratory 401

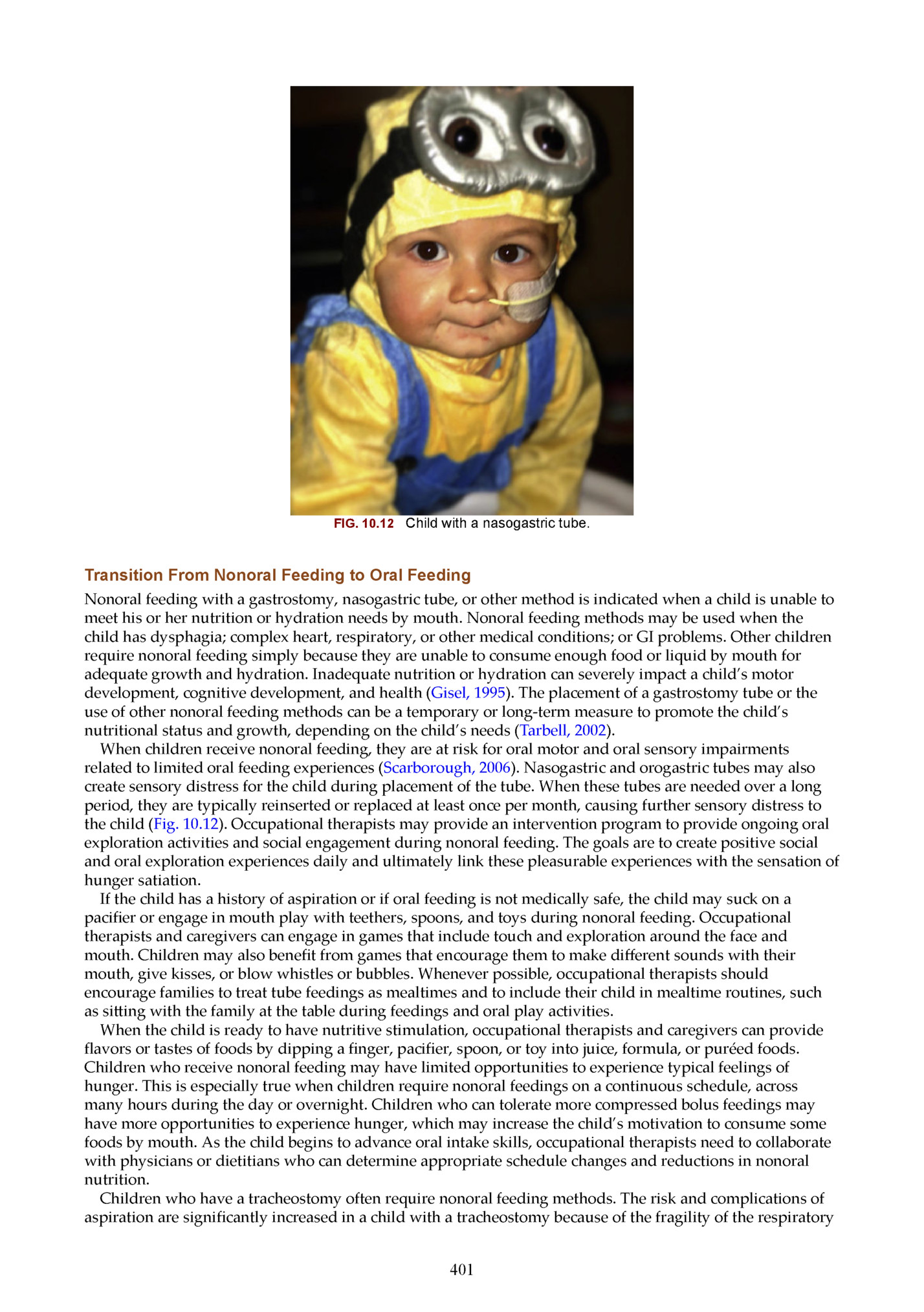

the changes in pressure created by the new opening in the laryngeal cavity or poor laryngeal mobility. Children with a tracheostomy may be ready for nutritive stimulation when they are able to manage their own saliva without frequent suctioning and can tolerate a speaking valve or cap, which may help create more normalized pharyngeal swallowing coordination (Gross 2003). Occupational therapists must collaborate with physicians and complete comprehensive assessments of swallowing before initiating nutritive oral feeding activities in children with a tracheostomy. Before receiving medical clearance for oral feeding, children with a tracheostomy will benefit from nonnutritive oral exploration and mouth play activities when oral feeding is not possible. Even when children are medically cleared and have sufficient oral motor skills and swallowing abilities to consume larger amounts of food by mouth, they may continue to demonstrate strong oral aversions, hypersensitivity, or refusal to engage in oral feeding activities. Transitioning from nonoral to oral feeding is a gradual process and may require a variety of oral sensory activities, skill development, and behavioral intervention over a period. This process is often complex and requires collaboration with physicians, dietitians, and other professionals (Research Note 10.3). Cleft Lip and Palate Approximately 1 in 700 infants is born with a cleft lip and/or cleft palate (Bessell, 2011). A cleft lip or cleft palate is a separation or hole in the oral structures typically joined together at midline during the early weeks of fetal development. A cleft lip is separation of the upper lip, which may be seen as a small indentation, or a larger opening that extends up to the nostril. A cleft palate is a separation of the anterior hard or posterior soft palate and may occur with or without a cleft lip (Fig. 10.13). Clefts in the lip and palate range in severity, may be unilateral or bilateral, and may be part of a larger constellation of medical problems associated with a specific syndrome, such as Pierre-Robin sequence, CHARGE (Coloboma of the eye, heart defects, atresia of the choanae, retardation of growth and development, and ear abnormalities and deafness) association, SmithLemli-Opi syndrome, Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, and orofaciodigital syndrome (Miller, 2011). Children born with clefts typically require one or more surgical procedures to repair the lip or palate. These surgeries may be scheduled at various times in the young child’s life, depending on other medical problems, growth and nutrition status of the child, and growth of the lip and/or palatal tissues. Additionally, the use of nasal alveolar molding (NAM) may be utilized prior to surgery with improved surgical repair outcomes reported. NAM is a nonsurgical way to reshape the gums, lips, and nostrils with a plastic plate before cleft lip and palate surgery. Presurgery molding may decrease the number of surgeries necessary, as it makes the cleft less severe (Grayson, 2005). Research Note 10.3 Pentiuk S. P. et al. (2011). Pureed by gastrostomy tube diet improves gagging and retching in children with fundoplication. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 35, 375–379. Abstract Children with feeding disorders requiring a gastronomy tube (G-tube) and Nissen fundoplication may develop gagging and retching following gastrostomy feedings. This study describes the development and use of a “pureed by gastrostomy tube” diet (PBGT) to treat those symptoms and provide adequate nutrition and hydration. Thirty-three children post-fundoplication surgery with symptoms of gagging and retching with G-tube feedings were selected from an interdisciplinary feeding team. An individualized PBGT diet was designed to meet the child’s nutritional goals. The child’s weight gain was recorded at each follow up visit. A telephone survey was performed to determine parents’ perceptions of the child’s symptoms and oral feeding. Results included 76% to 100% reduction in gagging and retching for 17 children, or 52%. 73% of children (24) were reported to have a >50% decrease in symptoms. No child had worsened symptoms. 19 children (57%) were reported to have an increase in oral intake on the PBGT diet. The authors concluded that a PBGT diet is an effective means of providing nutrition to children with feeding disorders, and that in children post-fundoplication surgery, a PBGT diet may decrease gagging and retching behaviors. Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice The authors describe common complications of fundoplications, as well as several common strategies that are employed to lessen these symptoms. The underlying pathogenesis of these complications, including gagging and retching, is multifactorial and not well-studied. A PBGT diet can decrease gagging and retching in children with feeding disorders after fundoplication surgery, as well as increase oral intake. The diet must be individualized to the child’s nutritional needs and requires an experienced dietitian who is able to create and modify the diet over time. 402

latching onto the bo le or breast, inefficient milk transfer, prolonged feeding times, milk leaking from the nose, and poor weight gain. Because of the lack of closure between the oral and nasal cavities, young infants with cleft lip or palate have difficulty or are unable to latch and create suction to express liquid during breastfeeding or bo le feeding (Morris, 2000). Infants born with clefts in the lip and palate, bilateral clefts, and syndromes that include other medical problems typically have more severe feeding problems. Infants born with only a minor cleft lip may be successful with breastfeeding or bo le feeding with a standard system, with only a few simple adaptations (Miller, 2011). Occupational therapists recommend compensatory positioning, adaptive feeding techniques, and specialized bo les for young infants with cleft lip or palate. Feeding the child in a more upright position (>60 degrees) may help improve milk transfer to the posterior oral cavity. Cheek and/or lip support may be recommended to help with gentle closure of a cleft lip to improve latching or suction during feeding. A variety of specialized bo les and nipples are available that use up-and-down compression movements (rather than suction) or allow the caregiver to squeeze the bo le to help extract and transfer milk. The Special Needs Feeder (previously called the Haberman Feeder) has a long, soft nipple and one-way valve that can deliver milk with li le to no oral suction required (Miller, 2011). The longer length of the nipple helps deposit the liquid toward the back of the mouth, beyond the cleft. The Dr. Brown’s Infant Paced Feeding Valve can be inserted into any standard Dr. Brown’s bo le/nipple system to improve an infant’s ability to use compression to extract milk from the bo le. Specialty feeding systems have a feature to allow the feeder to assist with milk transfer in synchrony with the infant’s sucking efforts. It is often suggested to use positioning adaptations and specialized bo le systems as a first approach. Infants with severe cleft lip and palate may require additional medical interventions, such as a nasal trumpet or palatal obturator, to be successful with oral feeding. These devices are costly, require custom fi ing, often need replacing as the infant grows larger, and may be challenging to use (Miller, 2011). FIG. 10.13 Cleft lip and palate. From: Silvestri: Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-PN® Examination, (7th Edition) 2018, St. Louis MO While breast/bo le feeding and nutritional challenges are usually the first obstacles for babies born with clefts, it is important to provide anticipatory guidance regarding introduction to spoon-feeding, cup drinking, and approach to care before and after surgical repair. Many surgical protocols include avoiding the 403

which means the infant should have practice with alternative means prior to planned procedures. After surgical repair of a cleft, occupational therapists may perform scar massage, initiate therapy activities to reduce oral hypersensitivity, and reassess the oral feeding method. Some children may have ongoing problems with food or liquid entering the nasal cavity during oral feeding. Interventions for this problem include evaluating which food or liquid textures are more challenging for the child, alternating bites of food with sips of liquid, suggesting more upright positioning during feeding, and recommending smaller sized bites of food or sips of liquid. Other Structural Anomalies Other structural anomalies affecting the feeding process include micrognathia, macroglossia, and ankyloglossia. Micrognathia is defined as a small recessed jaw. Macroglossia is a term used when the tongue is disproportionately large in comparison with the size of the mouth or jaw. Ankyloglossia, also referred to as tongue tie, is a congenital oral anomaly that may decrease the mobility of the tongue and is caused by an unusually short, thick, or anterior a achment connecting the tongue to the floor of the mouth. Occupational therapists need to consider the impact of the size and position of oral structures on respiration and oral movement pa erns during feeding. They may use different nipples, utensils, or positioning adaptations to help compensate for these structural differences. For example, infants with micrognathia may benefit from a prone or side-lying position to help draw the tongue into a more forward position, allowing improved respiration and nipple compression during bo le feeding. Infants with macroglossia may require adaptations to reduce tongue-thrusting movements and anterior food loss during feeding. Babies with limited range of tongue movement related to tongue tie should be further evaluated by a pediatric dentist or otolaryngologist (ENT) to determine need for surgical release or intervention. Tooth development is essential to support successful management of solid food textures. Dental anomalies and oral health can greatly impact a child’s willingness and ability to eat. Whether these anomalies are acquired or congenital, they can play a significant role in the occupational therapist’s intervention plan. For example, atypical dental development (missing teeth) may require modification of food textures to enable effective breakdown of food. Dental decay may limit a child’s interest in meals due to pain associated with chewing. This decay may also lead to the need for dental extractions, with additional implications for learning and success with the mechanics of eating. Structural anomalies of the larynx and esophagus include laryngeal clefts, esophageal strictures, tracheoesophageal fistula, and esophageal atresia. Laryngeal clefts vary in severity and are the result of a malformation of the tracheoesophageal septum in utero (Cohen, 2011). Tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia are both repaired surgically, often within the first few days of life. Children with a history of surgical repair to the esophagus are at increased risk of later developing esophageal stricture, a narrowing of the esophagus. Although these diagnoses are rare, children with structural anomalies of the esophagus are at increased risk for aspiration during swallowing, food refusal behaviors, delayed transition to textured foods, and poor esophageal motility (Baird, 2015). Esophageal motility describes how quickly foods and liquids move through the esophagus and empty into the stomach. Liquids and smooth, runny foods empty into the stomach more quickly than thick, fibrous, or more solid foods. Children who have a history of esophageal structural anomalies or esophageal phase swallow problems may have problems advancing to higher food textures because of decreased esophageal motility or function. Occupational therapists may recommend adapting food textures to maximize oral intake, alternating bites of food with sips of liquid to help clear the esophagus, slowing the pace of feeding, or encouraging a subsequent dry swallow after each bite of food to help compensate for delayed esophageal motility. Case Application: Occupational Therapy Intervention Considerations Case Example 10.1 provides an overview occupational therapy intervention for a child with feeding difficulties. A discussion of the evaluation findings, impressions, and intervention considerations are provided to illustrate occupational therapy to address feeding in practice. Evaluation Findings At Cooper’s feeding evaluation he was in good general health with no respiratory history or acute medical concerns. He has a history of constipation managed with MiraLAX. Cooper was well-nourished on a pediatric formula provided by his G-tube and his pediatrician’s growth records revealed weight at the 40th percentile and height at the 55th percentile for his age. Cooper is fed the majority of his nutritional intake 404

parents report that he is congested, and he often vomits mucus first thing. He rarely indicates that he is hungry during the day and he will accept a few crackers at a time and sips of water by mouth, which are the only items he requests. When his parents ask if he is hungry, Cooper fusses and refuses to eat. Cooper’s parents only had success with using television and videos to get him to eat, even his preferred snack foods. His gag response is easy to trigger and occurs with crying, coughing, activity, and some a empts to eat. Gagging at times results in vomiting. During the oral peripheral examination, Cooper presented with global low muscle tone, including his face, with his mouth gently open at rest and his tongue in a forward position. Mild to moderate drooling was observed, specifically when he was interested in a task or actively mouthing a toy. Cooper’s dental development is delayed as he has eight incisors present, but no molars have erupted yet. Cooper has a prolonged interest in mouthing and oral exploration, however his parents report that all a empts to brush his teeth result in crying, gagging, and on occasion, vomiting. Based on developmental evaluations, Cooper has delays in all areas including, gross motor, fine motor, speech-language, and self-help skills. He is mobile and started walking independently at 20 months. His pa erns of movement are influenced by his low muscle tone and he lacks graded control of movement. Cooper’s preferred position for play while si ing on the floor is W-si ing. He enjoys dump and fill play activities and throwing toys. He points, makes vocalizations, and uses gestures and facial expressions to communicate his wants and needs. Cooper is friendly, social, and is easy to engage in play. Case Example 10.1 Cooper Cooper is a 2-year-old boy referred for a feeding evaluation due to his parents’ concerns regarding gagging, choking, and food refusal. He has long-standing difficulties with growing and has a gastrostomy tube (G-tube) for supplemental nutrition. Currently, Cooper relies on his G-tube for the majority of his calories, however he is willing to eat small portions of preferred foods (goldfish crackers, veggie sticks) while watching his favorite videos on television. He continues to be very interested in oral exploration with toys and his parents state that he puts “everything” in his mouth. Cooper has li le interest in trying to use a spoon, but he is able to feed himself with his fingers independently. He drinks sips of water from a straw cup, with occasional coughing reported, however he refuses to drink formula or milk. Cooper receives physical therapy through early intervention services for delayed motor milestones and low muscle tone. He has been referred for a speech-language evaluation since he does not yet use single words or respond to simple requests and directions. Review of Cooper’s medical history revealed that Cooper was born full term, weighing 8 pounds, 4 ounces. Challenges during the newborn period included: low muscle tone, weak suck, gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and slow growth. Despite close follow-up by a gastroenterologist and medical treatment for GER, Cooper experienced frequent gagging and vomiting and over time self-limited his intake by bo le to 2 ounces at a time. Due to limited intake and growth concerns, Cooper’s medical team elected to introduce pureed foods at 4 months of age to supplement growth, improve reflux symptoms, and support Cooper’s feeding development. Due to Cooper’s low muscle tone and delayed motor skills, his parents held him in their arms in a semi-reclined position for spoon-feeding. He responded to purees with an increase in gagging and refusal and began to cry at every a empted meal. At 6 months of age, a G-tube was placed to support Cooper’s intake and growth, while still encouraging him to eat by mouth. Once the G-tube was placed, Cooper was fed continuous feedings overnight. His parents offered him foods and his formula during the day, but he showed li le interest in eating orally during waking hours. Cooper was included in family mealtimes and he reached for his parents’ foods. In order to preserve Cooper’s limited interest, they gave him any food that he wanted, without hesitation. During this period, Cooper showed an increase in gagging, choking, and spi ing out food, despite motivation to try his parents’ foods. He would gag or vomit if his parents pushed him to take a bite of pureed food. As a result, Cooper no longer wanted to participate in family meals and began to resist when requested to sit in the high chair at the table. His feeding difficulties created a stressful environment around mealtimes for both Cooper and his parents. Since Cooper was not really eating or drinking much volume, his parents did not insist that he continue to participate in family meals, that he follow a schedule, or sit at the table to eat. During the feeding observation, Cooper became upset when requested to sit at the table to eat. He refused preferred foods such as crackers, as well as nonpreferred foods, and he pushed his plate onto the floor. Once Cooper calmed away from the table, he played with his mother’s smartphone. While distracted with videos on the phone, Cooper held goldfish crackers and fed himself one at a time. He chewed with his mouth open and vertical jaw movements, but he did not lose any food forward from his mouth. He took a few sips of 405

and he had mild loss of water from his mouth while drinking. He ate four crackers and then refused to eat or drink further. Key Impressions From Evaluation Cooper’s feeding development has been impacted by his medical history, developmental delays, negative experiences with eating and altered daily living schedule (feeding and eating pa erns). • There are persistent concerns for gastrointestinal health with GER and constipation managed by a GI specialist. • Cooper was not referred for an instrumental evaluation of swallowing due to low suspicion for pharyngeal dysphagia. He has a good pulmonary health history and lack of significant clinical indicators (such as persistent coughing or choking when drinking) to suggest that swallow dysfunction is a contributing factor. • His feeding schedule is not consistent with a typical toddler’s feeding regime as he is fed all night long and grazes on small amounts of snack foods and water during the day. • Persistent gagging, vomiting, and learned oral hypersensitivity with feeding experiences and tooth brushing are noted. • Lack of oral feeding experience, typical mealtime experiences, and self-feeding opportunities have resulted in delayed oral motor skills and limited self-feeding abilities. • Cooper has developed maladaptive mealtime behaviors, including not staying at the table, refusal of most foods offered, pushing foods away, need for video distraction, gagging, crying, and occasional vomiting. • Global developmental delays and low muscle tone are limiting typical progression of feeding skills. • Stressful family mealtimes have resulted from Cooper’s behaviors and long-standing feeding challenges. Intervention Considerations Creating a Team: Who needs to be involved in Cooper’s feeding care plan? It was important to partner with Cooper’s GI physician and a pediatric dietitian to begin the process of transitioning G-tube feedings to a more typical toddler feeding schedule. These specialists provided input on issues related to tolerance, bolus feeding, and optimal nutrition. The long-term goal was to establish a schedule for meals and snacks (by tube and by mouth) during the day that aligned with his family’s daily routines and was appropriate for his age. Cooper’s primary care physician continued to monitor his overall health, growth, and development during the process and was updated on progress. The team recommended the family establish regular appointments with a pediatric dentist to support Cooper’s ability to tolerate oral care and hygiene through tooth brushing and routine dental visits. The occupational therapist collaborated with Cooper’s physical therapist to promote foundational skills that supported si ing at the table, participation in eating, and self-feeding. Mealtime Environment Considerations: In an effort to promote a healthy balance of self-care, work, and play for Cooper and support a family-centered approach, the therapist addressed creating a predictable and consistent schedule that the family was able to maintain at home. His schedule provided opportunities for structured mealtimes, time for supportive developmental activities and learning, and protected optimal time for sleep. While hunger was one consideration to promote Cooper’s intake, hunger provocation was not the initial goal for treatment. Rather, it was presumed that providing meals and snacks (including G-tube feedings) on a planned basis would create natural periods of hunger and satiety consistent with typical development. In general, the occupational therapist recommended that G-tube feedings be paired with eating by mouth, with the entire meal completed in a 20- to 30-minute period. Cooper needed a consistent, designated place to sit (such as the high chair or booster seat) and to eat with the family so that he could learn from the social context of mealtimes. All distractions, such as toys, books, videos, and television, were removed from the table and Cooper’s a ention was directed to foods, people at the table, and the mealtime routine. Motor Considerations: Cooper has low muscle tone throughout, and while he sat independently, his posture and alignment were best when he was provided with additional support from the high chair, with a five-point harness, tray, and foot rests in place. This gave him support so that Cooper was able to engage in exploration of foods, utensils, and self-feeding development. Remaining seated while eating and drinking is the safest practice for children and this “rule” was modeled by the family to help Cooper stay at the table for supervised meals and snacks. Based on his success with self-feeding when given proximal support, the therapist trialed adaptive feeding equipment including utensils with broad handles, a suction cup bowl, and a sippy cup with handles. 406

Fleepit Digital © 2021