The Intentional Relationship Working With Children and Families Jane O’Brien, and Renee Taylor GUIDING QUESTIONS 1. What is therapeutic use of self? 2. How do occupational therapists develop and sustain therapeutic relationships with children and families? 3. What types of therapeutic styles (modes) exist and how are they used in occupational therapy practice with children and youth? 4. How do occupational therapists resolve conflicts that arise in therapy? 5. What strategies and techniques can occupational therapists use to develop effective therapeutic use of self? KEYWORDS Activity focusing Advocating Body language Client-centered approach Collaborating Communication Cultural competence Empathizing Encouraging Enduring characteristics Inevitable interpersonal events Instructing Intentional Relationship Model (IRM) Interpersonal focusing Interpersonal reasoning Mindful empathy Problem solving Professionalism Therapeutic relationship Therapeutic use of self Self-awareness Style Situational characteristics 224

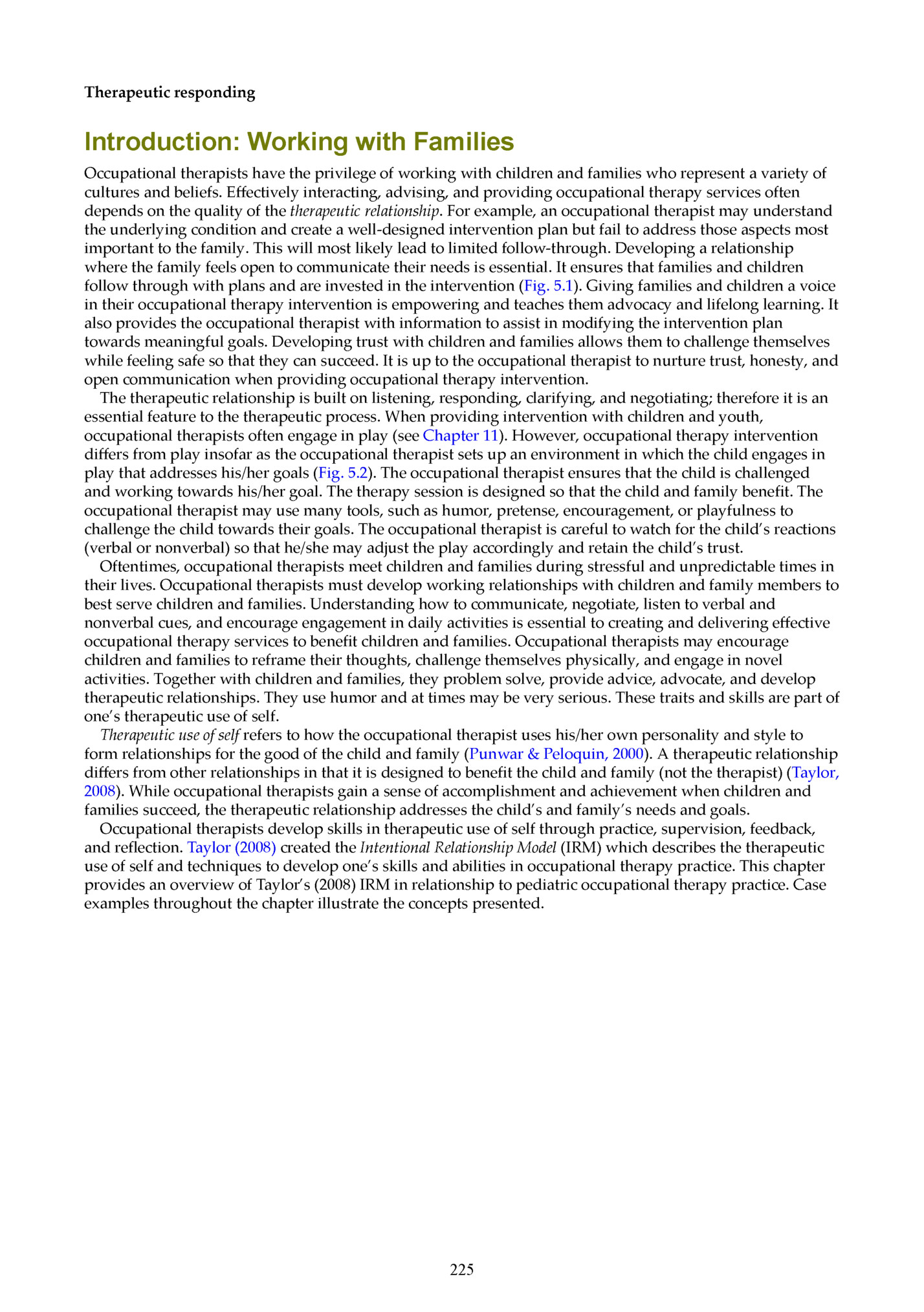

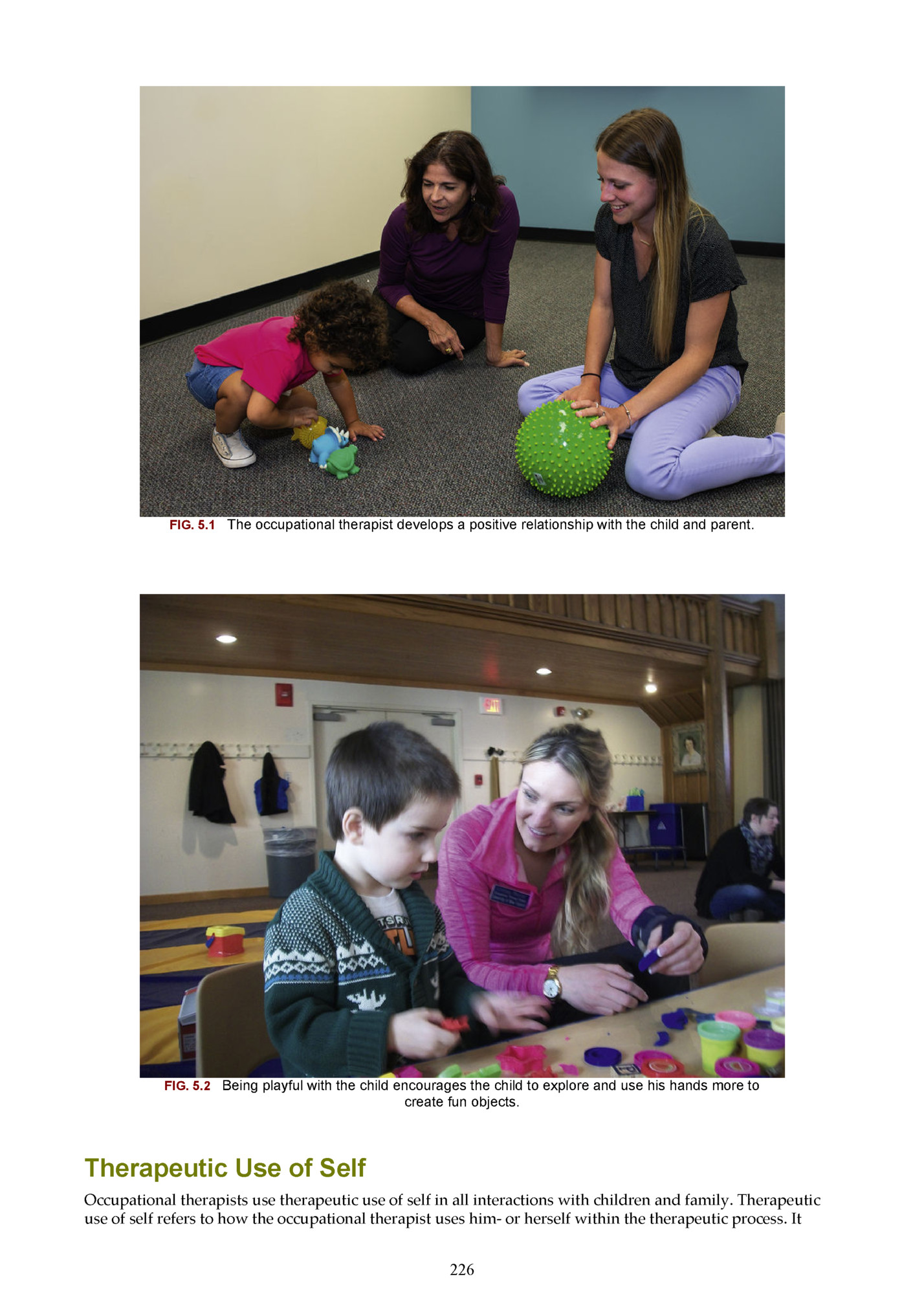

Introduction: Working with Families Occupational therapists have the privilege of working with children and families who represent a variety of cultures and beliefs. Effectively interacting, advising, and providing occupational therapy services often depends on the quality of the therapeutic relationship. For example, an occupational therapist may understand the underlying condition and create a well-designed intervention plan but fail to address those aspects most important to the family. This will most likely lead to limited follow-through. Developing a relationship where the family feels open to communicate their needs is essential. It ensures that families and children follow through with plans and are invested in the intervention (Fig. 5.1). Giving families and children a voice in their occupational therapy intervention is empowering and teaches them advocacy and lifelong learning. It also provides the occupational therapist with information to assist in modifying the intervention plan towards meaningful goals. Developing trust with children and families allows them to challenge themselves while feeling safe so that they can succeed. It is up to the occupational therapist to nurture trust, honesty, and open communication when providing occupational therapy intervention. The therapeutic relationship is built on listening, responding, clarifying, and negotiating; therefore it is an essential feature to the therapeutic process. When providing intervention with children and youth, occupational therapists often engage in play (see Chapter 11). However, occupational therapy intervention differs from play insofar as the occupational therapist sets up an environment in which the child engages in play that addresses his/her goals (Fig. 5.2). The occupational therapist ensures that the child is challenged and working towards his/her goal. The therapy session is designed so that the child and family benefit. The occupational therapist may use many tools, such as humor, pretense, encouragement, or playfulness to challenge the child towards their goals. The occupational therapist is careful to watch for the child’s reactions (verbal or nonverbal) so that he/she may adjust the play accordingly and retain the child’s trust. Oftentimes, occupational therapists meet children and families during stressful and unpredictable times in their lives. Occupational therapists must develop working relationships with children and family members to best serve children and families. Understanding how to communicate, negotiate, listen to verbal and nonverbal cues, and encourage engagement in daily activities is essential to creating and delivering effective occupational therapy services to benefit children and families. Occupational therapists may encourage children and families to reframe their thoughts, challenge themselves physically, and engage in novel activities. Together with children and families, they problem solve, provide advice, advocate, and develop therapeutic relationships. They use humor and at times may be very serious. These traits and skills are part of one’s therapeutic use of self. Therapeutic use of self refers to how the occupational therapist uses his/her own personality and style to form relationships for the good of the child and family (Punwar & Peloquin, 2000). A therapeutic relationship differs from other relationships in that it is designed to benefit the child and family (not the therapist) (Taylor, 2008). While occupational therapists gain a sense of accomplishment and achievement when children and families succeed, the therapeutic relationship addresses the child’s and family’s needs and goals. Occupational therapists develop skills in therapeutic use of self through practice, supervision, feedback, and reflection. Taylor (2008) created the Intentional Relationship Model (IRM) which describes the therapeutic use of self and techniques to develop one’s skills and abilities in occupational therapy practice. This chapter provides an overview of Taylor’s (2008) IRM in relationship to pediatric occupational therapy practice. Case examples throughout the chapter illustrate the concepts presented. 225

FIG. 5.2 Being playful with the child encourages the child to explore and use his hands more to create fun objects. Therapeutic Use of Self Occupational therapists use therapeutic use of self in all interactions with children and family. Therapeutic use of self refers to how the occupational therapist uses him- or herself within the therapeutic process. It 226

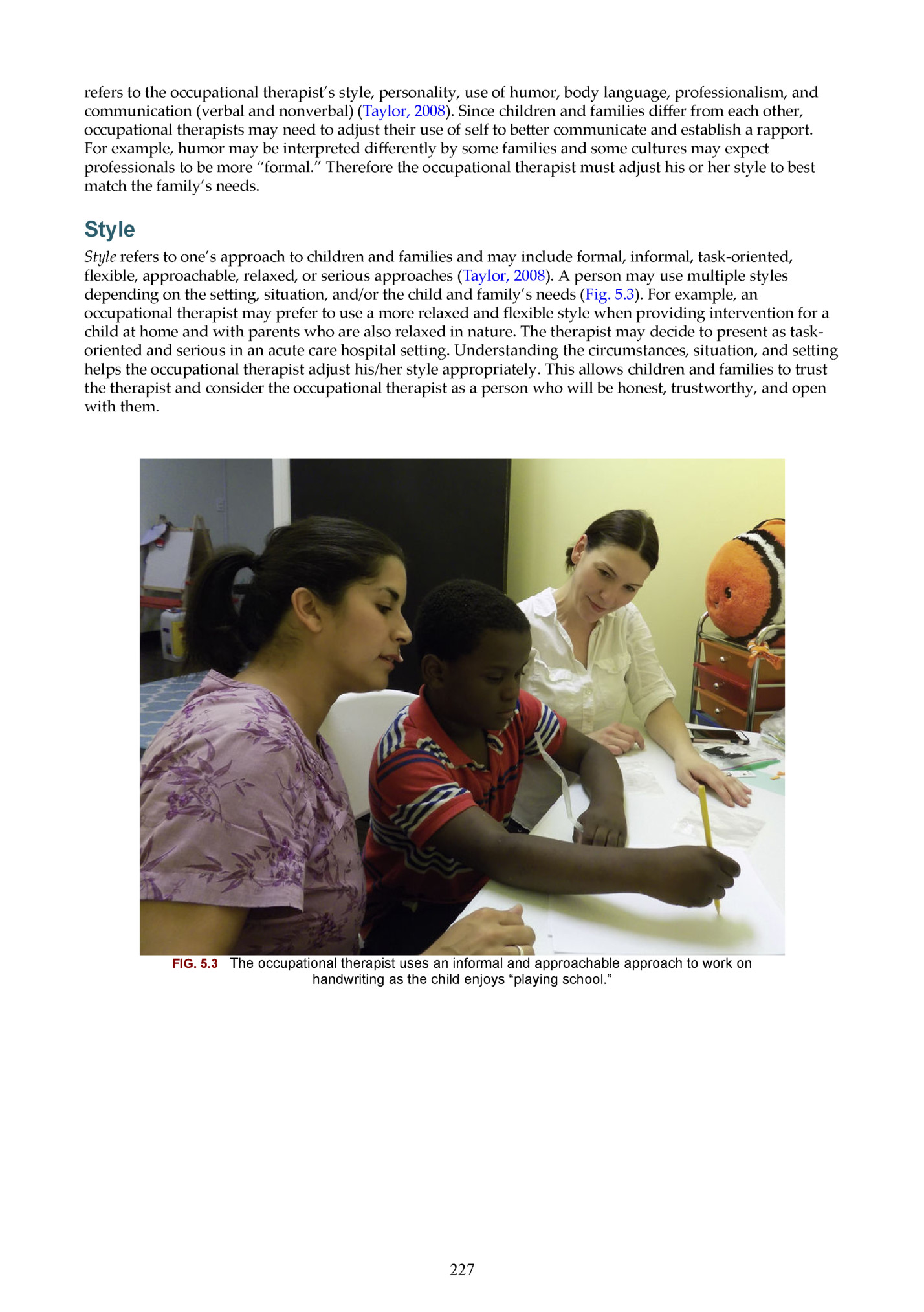

communication (verbal and nonverbal) (Taylor, 2008). Since children and families differ from each other, occupational therapists may need to adjust their use of self to be er communicate and establish a rapport. For example, humor may be interpreted differently by some families and some cultures may expect professionals to be more “formal.” Therefore the occupational therapist must adjust his or her style to best match the family’s needs. Style Style refers to one’s approach to children and families and may include formal, informal, task-oriented, flexible, approachable, relaxed, or serious approaches (Taylor, 2008). A person may use multiple styles depending on the se ing, situation, and/or the child and family’s needs (Fig. 5.3). For example, an occupational therapist may prefer to use a more relaxed and flexible style when providing intervention for a child at home and with parents who are also relaxed in nature. The therapist may decide to present as taskoriented and serious in an acute care hospital se ing. Understanding the circumstances, situation, and se ing helps the occupational therapist adjust his/her style appropriately. This allows children and families to trust the therapist and consider the occupational therapist as a person who will be honest, trustworthy, and open with them. FIG. 5.3 The occupational therapist uses an informal and approachable approach to work on handwriting as the child enjoys “playing school.” 227

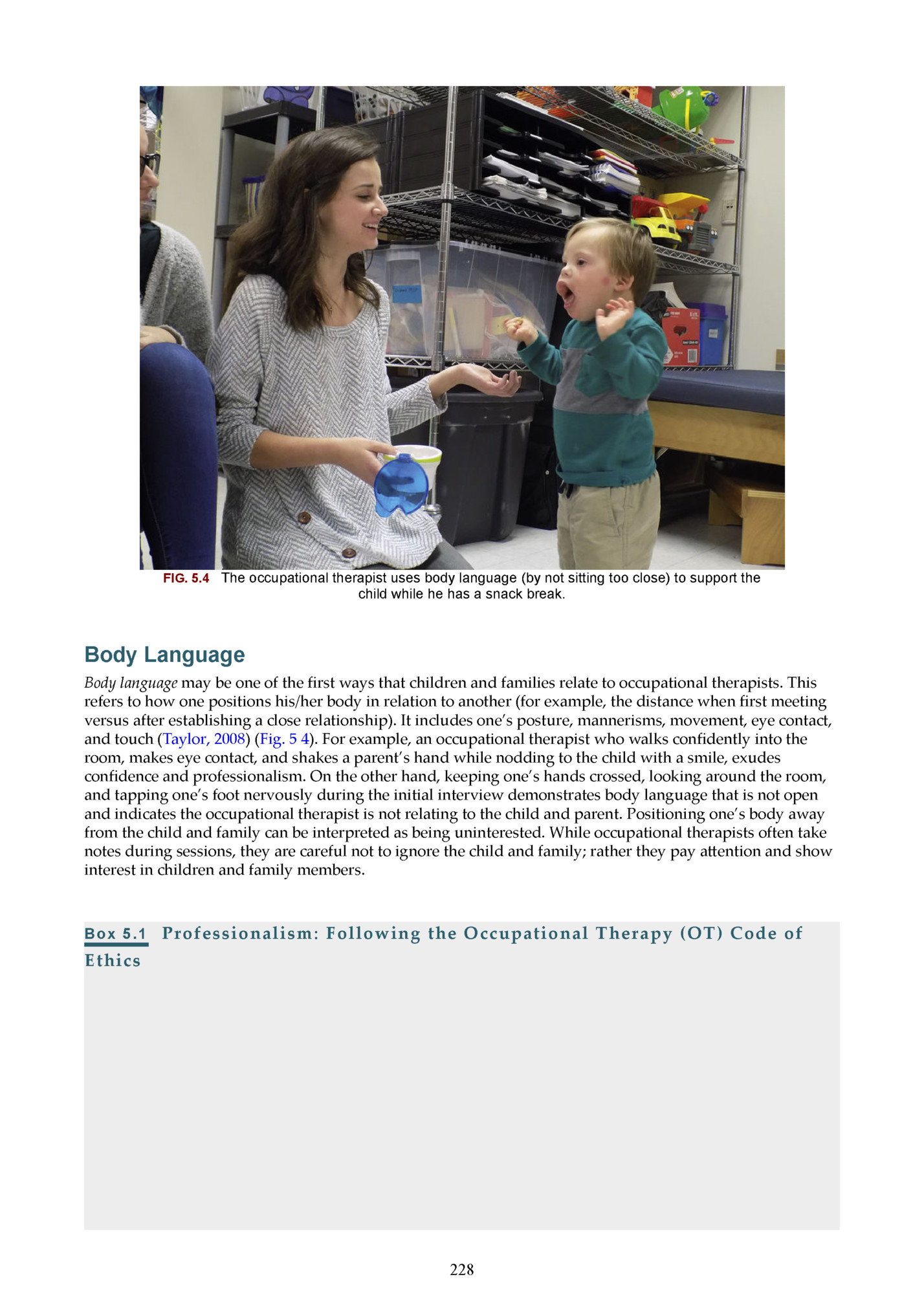

child while he has a snack break. Body Language Body language may be one of the first ways that children and families relate to occupational therapists. This refers to how one positions his/her body in relation to another (for example, the distance when first meeting versus after establishing a close relationship). It includes one’s posture, mannerisms, movement, eye contact, and touch (Taylor, 2008) (Fig. 5 4). For example, an occupational therapist who walks confidently into the room, makes eye contact, and shakes a parent’s hand while nodding to the child with a smile, exudes confidence and professionalism. On the other hand, keeping one’s hands crossed, looking around the room, and tapping one’s foot nervously during the initial interview demonstrates body language that is not open and indicates the occupational therapist is not relating to the child and parent. Positioning one’s body away from the child and family can be interpreted as being uninterested. While occupational therapists often take notes during sessions, they are careful not to ignore the child and family; rather they pay a ention and show interest in children and family members. Box 5.1 Professionalism: Following the Occupational Therapy (OT) Code of Ethics 228

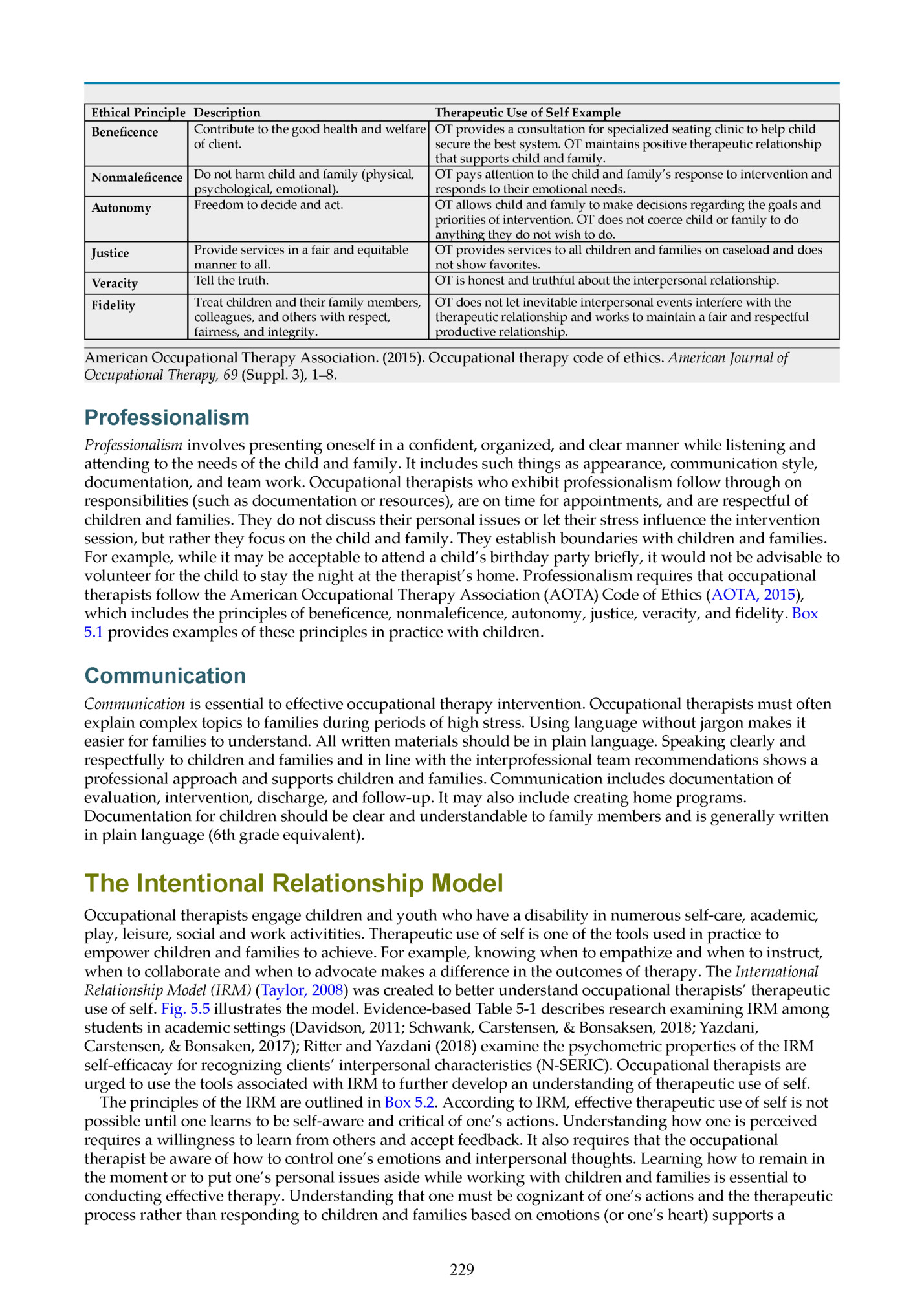

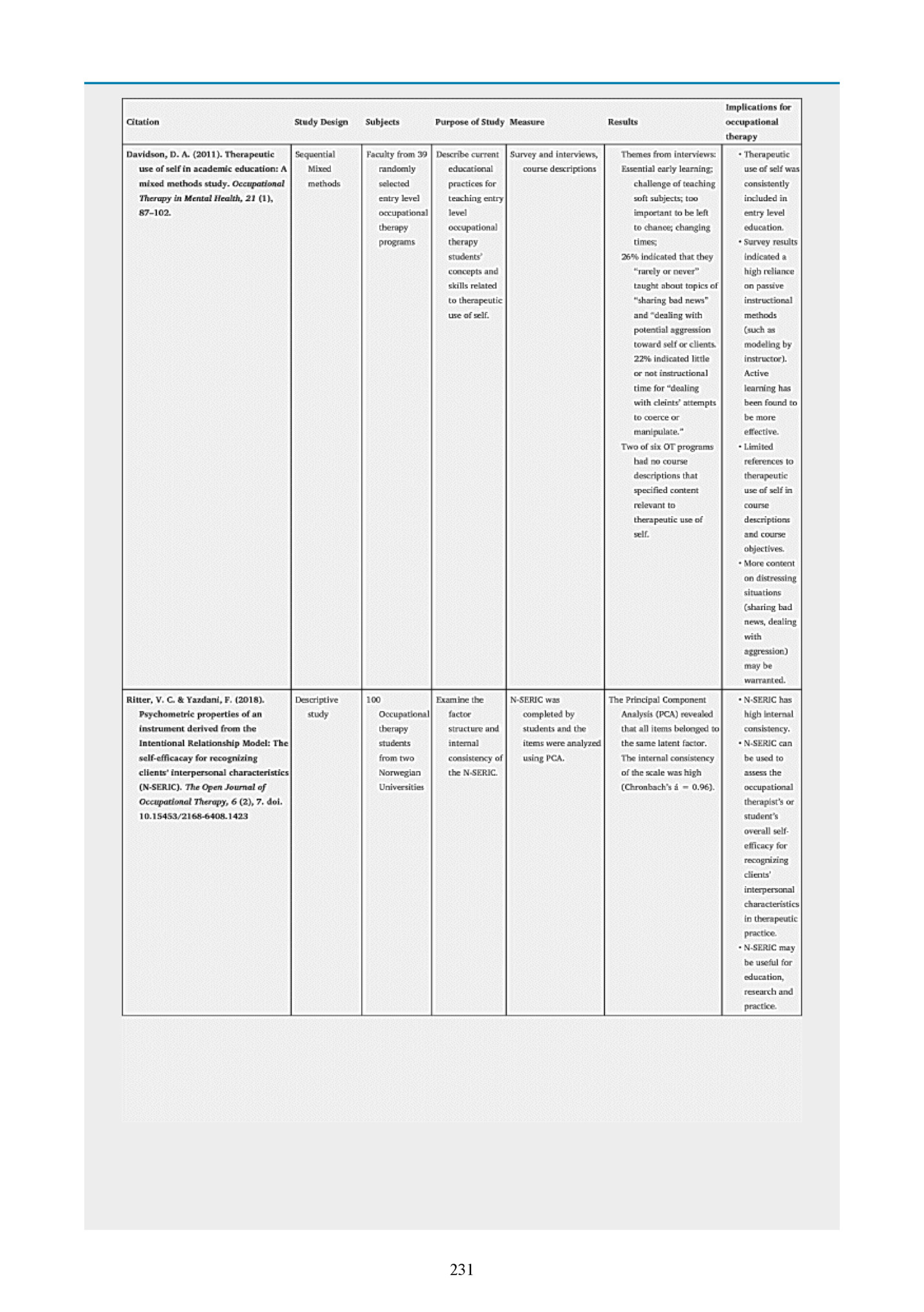

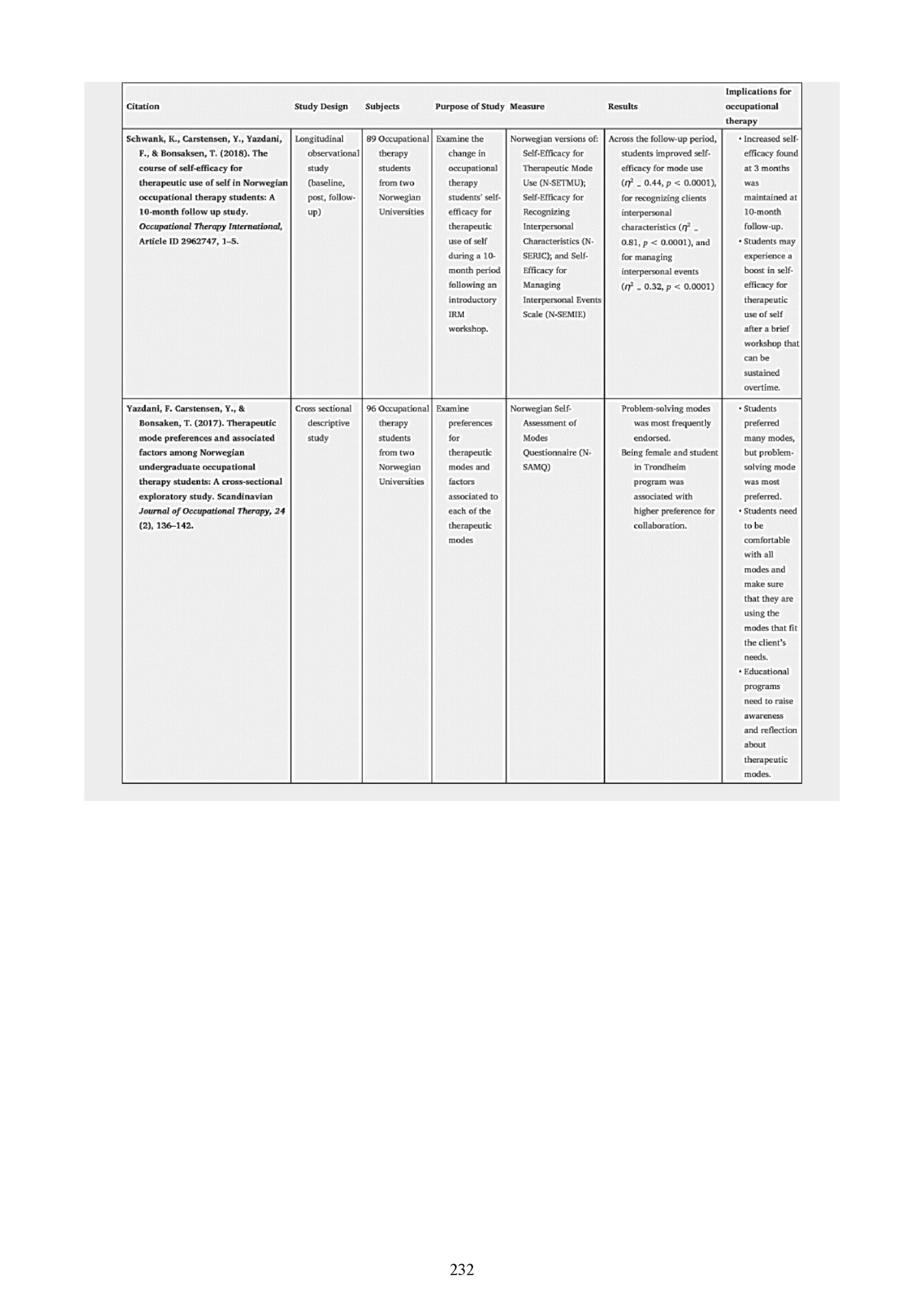

Therapeutic Use of Self Example Contribute to the good health and welfare OT provides a consultation for specialized seating clinic to help child Beneficence of client. secure the best system. OT maintains positive therapeutic relationship that supports child and family. Do not harm child and family (physical, OT pays a ention to the child and family’s response to intervention and Nonmaleficence psychological, emotional). responds to their emotional needs. Freedom to decide and act. OT allows child and family to make decisions regarding the goals and Autonomy priorities of intervention. OT does not coerce child or family to do anything they do not wish to do. Provide services in a fair and equitable OT provides services to all children and families on caseload and does Justice manner to all. not show favorites. Tell the truth. OT is honest and truthful about the interpersonal relationship. Veracity Fidelity Treat children and their family members, colleagues, and others with respect, fairness, and integrity. OT does not let inevitable interpersonal events interfere with the therapeutic relationship and works to maintain a fair and respectful productive relationship. American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). Occupational therapy code of ethics. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69 (Suppl. 3), 1–8. Professionalism Professionalism involves presenting oneself in a confident, organized, and clear manner while listening and a ending to the needs of the child and family. It includes such things as appearance, communication style, documentation, and team work. Occupational therapists who exhibit professionalism follow through on responsibilities (such as documentation or resources), are on time for appointments, and are respectful of children and families. They do not discuss their personal issues or let their stress influence the intervention session, but rather they focus on the child and family. They establish boundaries with children and families. For example, while it may be acceptable to a end a child’s birthday party briefly, it would not be advisable to volunteer for the child to stay the night at the therapist’s home. Professionalism requires that occupational therapists follow the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Code of Ethics (AOTA, 2015), which includes the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, justice, veracity, and fidelity. Box 5.1 provides examples of these principles in practice with children. Communication Communication is essential to effective occupational therapy intervention. Occupational therapists must often explain complex topics to families during periods of high stress. Using language without jargon makes it easier for families to understand. All wri en materials should be in plain language. Speaking clearly and respectfully to children and families and in line with the interprofessional team recommendations shows a professional approach and supports children and families. Communication includes documentation of evaluation, intervention, discharge, and follow-up. It may also include creating home programs. Documentation for children should be clear and understandable to family members and is generally wri en in plain language (6th grade equivalent). The Intentional Relationship Model Occupational therapists engage children and youth who have a disability in numerous self-care, academic, play, leisure, social and work activitities. Therapeutic use of self is one of the tools used in practice to empower children and families to achieve. For example, knowing when to empathize and when to instruct, when to collaborate and when to advocate makes a difference in the outcomes of therapy. The International Relationship Model (IRM) (Taylor, 2008) was created to be er understand occupational therapists’ therapeutic use of self. Fig. 5.5 illustrates the model. Evidence-based Table 5-1 describes research examining IRM among students in academic se ings (Davidson, 2011; Schwank, Carstensen, & Bonsaksen, 2018; Yazdani, Carstensen, & Bonsaken, 2017); Ri er and Yazdani (2018) examine the psychometric properties of the IRM self-efficacay for recognizing clients’ interpersonal characteristics (N-SERIC). Occupational therapists are urged to use the tools associated with IRM to further develop an understanding of therapeutic use of self. The principles of the IRM are outlined in Box 5.2. According to IRM, effective therapeutic use of self is not possible until one learns to be self-aware and critical of one’s actions. Understanding how one is perceived requires a willingness to learn from others and accept feedback. It also requires that the occupational therapist be aware of how to control one’s emotions and interpersonal thoughts. Learning how to remain in the moment or to put one’s personal issues aside while working with children and families is essential to conducting effective therapy. Understanding that one must be cognizant of one’s actions and the therapeutic process rather than responding to children and families based on emotions (or one’s heart) supports a 229

understand another person’s underlying emotions and feelings while remaining objective. Occupational therapists work with a variety of children and families who require different approaches. Since occupational therapists have their own style and approach, they must expand their knowledge base to be able to work with different people. Essentially, an occupational therapist cannot expect one approach to work with everyone. Instead the occupational therapist must be flexible with how they approach children and families. Therapeutic interactions require the occupational therapist to have a solid foundation of abilities and remain true to one’s core values and professional ethics. Staying true to the profession’s philosophy and facilitating occupational performance in children is essential to any therapeutic interaction. Furthermore, occupational therapists using a client-centered approach understand, value, and respect the child’s and family’s culture. Cultural competence refers to a knowledge and ability to understand and interact effectively with people of different cultures (SAMSHA, 2016). In occupational therapy, this may mean asking questions to be er understand how the child and family views and practices traditions or beliefs from their culture as that influences the intervention plan. Taylor, Lee and Kielhofner (2010) conducted a nationwide study to identify the modes occupational therapists used most frequently and whether therapists varied their modes of interacting with clients when the characteristics of clients vary (See Research Note 5.1). They found that modes were used (from most to least) as follows: encouraging, collaborating, problem-solving, instructing and emphathizing. E v i d e n c e - b a s e d Ta b l e 5 - 1 Studies Examining the Intentional Relationship Model (IRM) 230

Fleepit Digital © 2021